Carmen Marin:

Interlacing Sight and Paint

Raphy Sarkissian

Carmen Marin, Taupe Sky (To Paul Cézanne), 2022. Acrylic on linen, 51 by 32 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

“My paintings stem from my imagination that is nonetheless entrapped in the perplexing images in the caves of Lascaux, the evocative paintings of Cézanne and Giacometti, and the timelessness of Surrealism. The Heroes exhibition of Georg Baselitz I saw in Rome in 2017 had the most powerful impact on me.” These words of Carmen Marin shed light on several groups of partly-figurative paintings executed over the past five years. Confronting the viewer with a tone of mysticism, a given work by Marin is an embodiment of Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s concept of a primordial world: a pre-human world that is in a fragmentary, unending and incessant process of entering human perception.

Based in Romania and working in a frequently sunlit attic studio in the Obor district of Bucharest, Marin has established a distinctive pictorial language that often blurs the lines between recognizable and indeterminate forms. Within the practice of Marin, the intriguing tension between figuration and abstraction, manifesting the phenomenological junctions between the individual and the world, compels dialogues with works by the progenitors of modernism and contemporary artists. Through experimentation with the themes of landscape, portraiture, still life and overarching visual narratives, Marin has been realizing imposing paintings that provide the observer with wondrous visual encounters and call forth expansive possibilities of interpretation.

Piet Mondrian, Willow Grove: Impression of Light and Shadow, ca. 1905. Oil on canvas, 14 3/4 by 19 inches. Courtesy of the Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas.

Painted in April 2022, Taupe Sky (To Paul Cézanne) is an arresting landscape vista constructed through a structurally organized network of brushstrokes, rhythmic markings and sweeping curves. Here brisk, short and roughly parallel strokes in clusters of pale teal, olive, deep greens and black appear as hints of shrubs that recede toward a horizon. Above, the grayish sky conveys a sense of illumination through patches in shades of cream, ecru, muted celadon, light blue and pale pink. The dispersing apparition of a tree in the right foreground is echoed on the left through sinuous vertical figures that suggest abstraction as a component of the phenomenon of vision’s grasp of the world. Within this illusory pictorial space, sky and earth have been entwined, transforming one another through coloristic distinctions and interchanges. This recognizable yet not illusionistic painting of Marin brings to mind the words of Merleau-Ponty on Paul Cézanne’s complex method of painting landscapes: “The task before him was, first, to forget all he had ever learned from science and, second, through these sciences to recapture the structure of the landscape as an emerging organism.”[1]

Paul Cézanne, Morning in Provence, ca. 1900-6. Oil on canvas, 32 by 24 7/8 inches. Courtesy of the Buffalo AKG Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York.

The pictorial composition of Marin’s Taupe Sky (To Paul Cézanne) recalls Piet Mondrian’s exuberant modernist landscape Willow Grove: Impression of Light and Shadow (ca. 1905) at the Dallas Museum of Art. In this painting of Marin, the rose gold, bronze, brass and warm green brushstrokes of Mondrian have been replaced by the frostiness of platinum, silver and chrome, along with interwoven and directional touches of greens. Here nature has been distilled further from its recognizable figures, with treatments of color and distortions of perspective that evoke Cézanne’s Morning in Provence (ca. 1900-6) at the Buffalo AKG Art Gallery in New York. In this highly abstracted landscape painting of Cézanne, patches of blues, greens and yellows embody the transience of both nature and the imagery within vision. The isolated tree of Cézanne appears recurrently in Marin’s painting, where forms are delineated liberally and register as being suggestive of the temporal instability of visual perception. In these three paintings by Marin, Mondrian and Cézanne, the dialectic between the brushstroke and the visually perceived world permeates them with phenomenological gravitas.

Carmen Marin, Aqueduct (To Paul Cézanne), 2022. Acrylic on linen, 28 by 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Just as this seemingly phantasmic interplay between mimesis and its abstracted antithesis would characterize Cézanne’s radically new pictorial language beginning in the mid-1870s, such paintings of Marin as Aqueduct (To Paul Cézanne), Green in L’Estaque/Olive in Obor (To Paul Cézanne), and Without Boulder (To Paul Cézanne), all dated 2022, manifest themselves as surfaces of perpetual transformation that are suspended between Cézanne’s diagonally applied parallel brushstrokes and entirely abstracted gestural improvisations through the medium of acrylic on linen. Viewing these vibrant landscapes of Marin, it is not hard to recall so many of Cézanne’s paintings that dismantle the conventional spatial devices set forth at the outset of the Renaissance period. As these paintings of Marin reveal alternative instances of abstraction, their figurative entities unfold the thoughts of Merleau-Ponty on the physiological process of visual perception: “My experiences of the world are integrated into one single world as the double image merges into the one thing, when my finger stops pressing upon my eyeball. I do not have one perspective, then another, and between them a link brought about by the understanding, but each perspective merges into the other.”[2]

Carmen Marin, Rumination, 2021. Acrylic on linen, 35 by 24 inches. Courtesy of Sean Scully and Liliane Tomasko, New York.

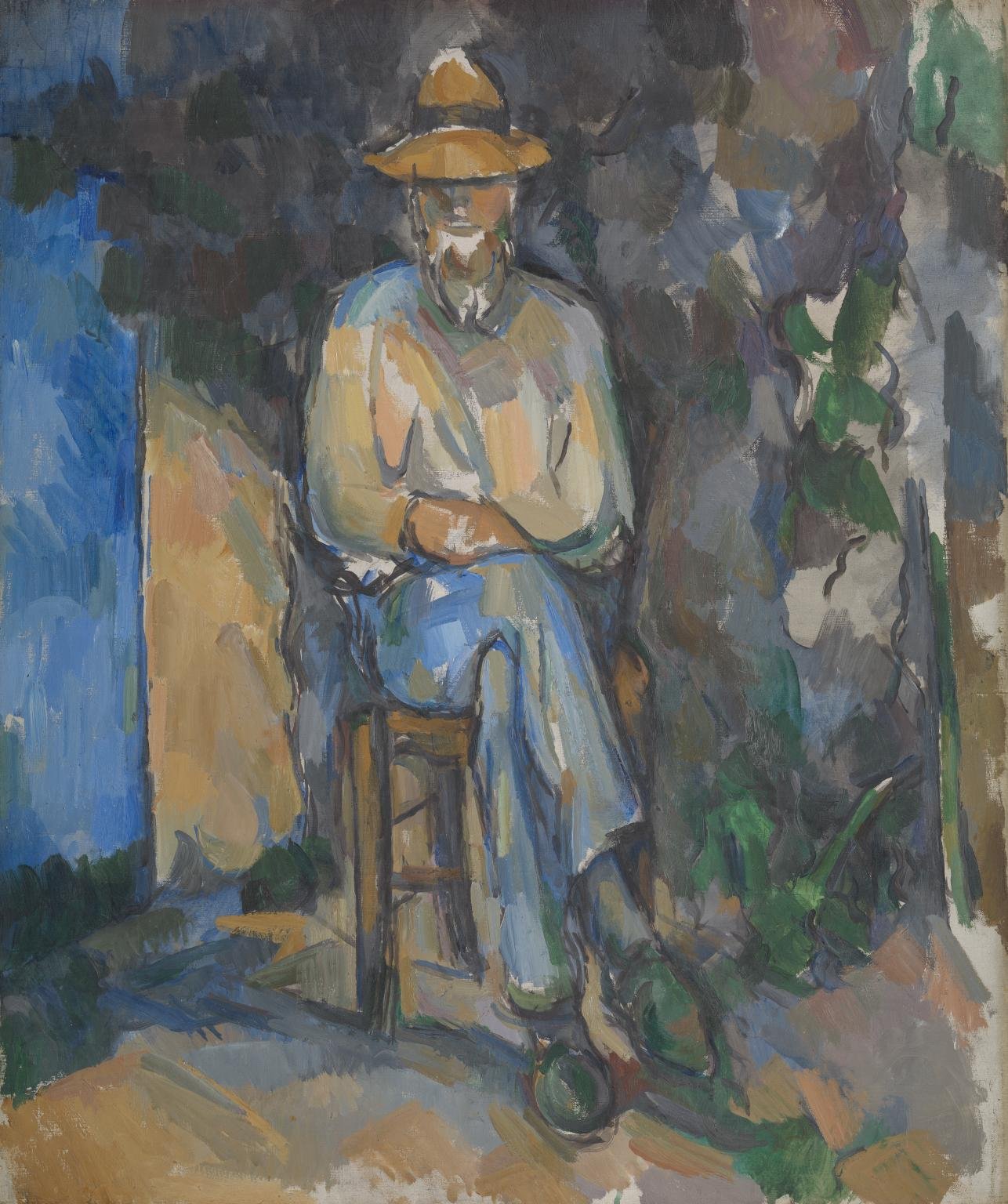

Seen from behind, the seated female figure in Marin’s entrancing Rumination (2021) appears significantly poised within an otherwise gesturally and chromatically frenzied panoramic realm whose palette reverberates the spellbinding mix of blues and greens of Cézanne’s absorbing Lac d’Annecy (1896) at the Courtauld Gallery in London. Thematically, this painting of Marin conjures up Cézanne’s highly abstracted yet considerably recognizable imagery in The Gardener Vallier (1905-6) at the Tate. While hinting at Cézanne’s outstanding Mont Saint-Victoire (1902-6) at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the spatial structure in Rumination considerably dissolves the pictorial logic of figure and ground relations of the background. Having articulated nature and sky by the sumptuous layering of paint and vibrant flashes of whites, greens and blues in accelerated speeds of brushwork, the background scenery of Rumination recalls the legendary visual languages of Willem de Kooning and Joan Mitchell. In turn, the presence of the human figure in the foreground recalls Merleau-Ponty’s thoughts on Cézanne’s primeval drive to seize the flux and temporality of visual perception: “We live in the midst of man-made objects, among tools, in houses, streets, cities, and most of the time we see them only through the human actions which put them to use. We become used to think that all this exists necessarily and unshakably. Cézanne’s painting suspends these habits of thought and reveals the base of inhuman nature upon which man has installed himself.”[3]

Paul Cézanne, The Gardener Vallier, 1905-6. Oil on canvas, 25 3/4 by 21 5/8 inches. Courtesy of the Tate, London.

Carmen Marin, Antithetical, 2021. Acrylic on linen, 28 by 24 inches. Private collection, Bucharest, Romania.

A sense of austerity predominates the purposefully unfinished facial formation of Antithetical (2021), a partially represented portrait of a female figure caught up between a sense of asceticism conveyed through the stare of the eyes and the opulence of receding floral arrangements in shades of cobalt blue. This mostly abstracted face in pale peach is echoed in the picture’s vacant background that is nonetheless a pale field of gestural marks in shades of beige. Figure and ground here convey a sense of the interchangeable, whereby body and space register as primordial reciprocities. This painting of Marin presents itself to the viewer as yet another pictorial counterpart to the words of Merleau-Ponty: “A face expresses something only through the arrangements of the colours and lights which make it up, the meaning of the gaze being not behind the eyes, but in them, and a touch of colour more or less is all the painter needs in order to transform the facial expression of a portrait.”[4]

Carmen Marin, Beyond Figuration, 2023. Acrylic on linen, 35 7/16 by 47 1/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Carmen Marin, Among the Chairs, 2022. Acrylic on linen, 26 by 20 inches. Private collection, Bucharest, Romania.

Unrestrained expressive marks in deep lilac and turquoise emblematize a floral arrangement within a space containing parts of a dinner table surrounded by chairs. White impasto defines the background and the tablecloth, blanketing the space with a sense of freshly fallen snow. With the rules of conventional perspective having been abandoned, Marin’s Among the Chairs (2022) brings to mind Merleau-Ponty’s observations of our perceptual experience of the world: “I open my eyes on to my table, and my consciousness is flooded with colour and confused reflections; it is hardly distinguishable from what is offered to it; it spreads out, through its accompanying body, into the spectacle which so far is not a spectacle of anything. Suddenly, I start to focus my eyes on the table which is not yet there, I begin to look into the distance while there is as yet no depth, my body centers itself on an object which is still only potential, and so disposes its sensitive surfaces as to make it a present reality.”[5] Marin’s abandonment of perspectival representation recurs in Beyond Figuration (2023). Four golden yellow daffodils contained within a powder blue vase punctuate the hallucinatory space of a dining room. Here the fragmented imagery of a table and its surrounding chairs is constructed through rectilinear gestural marks that charge the pictorial space with everchanging intimations of semblance.

Carmen Marin, The Fight, 2021. Acrylic on linen, 28 by 67 inches. Private collection, New York.

The Fight (2022) of Marin imparts a sense of existential atavism. Depicting a male figure in a recumbent position, Marin has concurrently delineated and disintegrated the body's inherent unity through painterly gestures that construct human resemblance. Below the chest, the figure is supplemented by means of a plethora of terse and hectic brushstrokes in black upon a bare white ground. This representation of the body reveals the corpus as an entity whose contiguity to the outside world is as delimited as it is integrated. Engulfed by wilting sunflowers formed through unstructured smears of paint in yellow, blue, orange and maroon, The Fight summons the viewer’s attention to the medium of painting so as to reveal a human figure as an embodiment of the phenomenological investigation of Merleau-Ponty: “My body is the fabric into which all objects are woven, and it is, at least in relation to the perceived world, the general instrument of any ‘comprehension.’”[6]

The painterly style that Carmen Marin has engineered carries with it a sense of the primordial, where paint and sight interlace figuration and abstraction.

Notes

1. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “Cézanne’s Doubt,” in The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader: Philosophy and Painting, ed. Galen A. Johnson (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1993), p. 67.

2. Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (1962; London: Routledge, 1995), p. 329.

3. Merleau-Ponty, “Cézanne’s Doubt,” p. 66.

4. Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, p. 322.

5. Merleau-Ponty, p. 239.

6. Merleau-Ponty, p. 284.