Ford Crull:

Accumulations

Exhibition Review | May 2019 | Raphy Sarkissian

Ford Crull, White Light, White Heat, 2013. Oil and wax on canvas, 68 by 60 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Klee, Angelus Novus (New Angel), 1920.

Oil transfer and watercolor on paper, 12.5 by 9.53 inches. Courtesy of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel.

Lush brushstrokes, sumptuous smears, crashing waves of color, violent scratches, partly obliterated marks, translucent layers of paint, undulations and swirls, autonomous letters and pictograms, insinuations of graffiti and automatic drawing: these are the primary elements through which Ford Crull renders his paintings highly poetic and Baudelairean, inviting the beholder to read a given picture open-endedly on the one hand, while it unequivocally conjures up instances of such instrumental currents of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as symbolism, surrealism and abstract expressionism—even pop art to a certain extent when we encounter his iconic hearts. Yet Crull trenchantly reincarnates aspects of these currents as voices of our time through his singular manner.

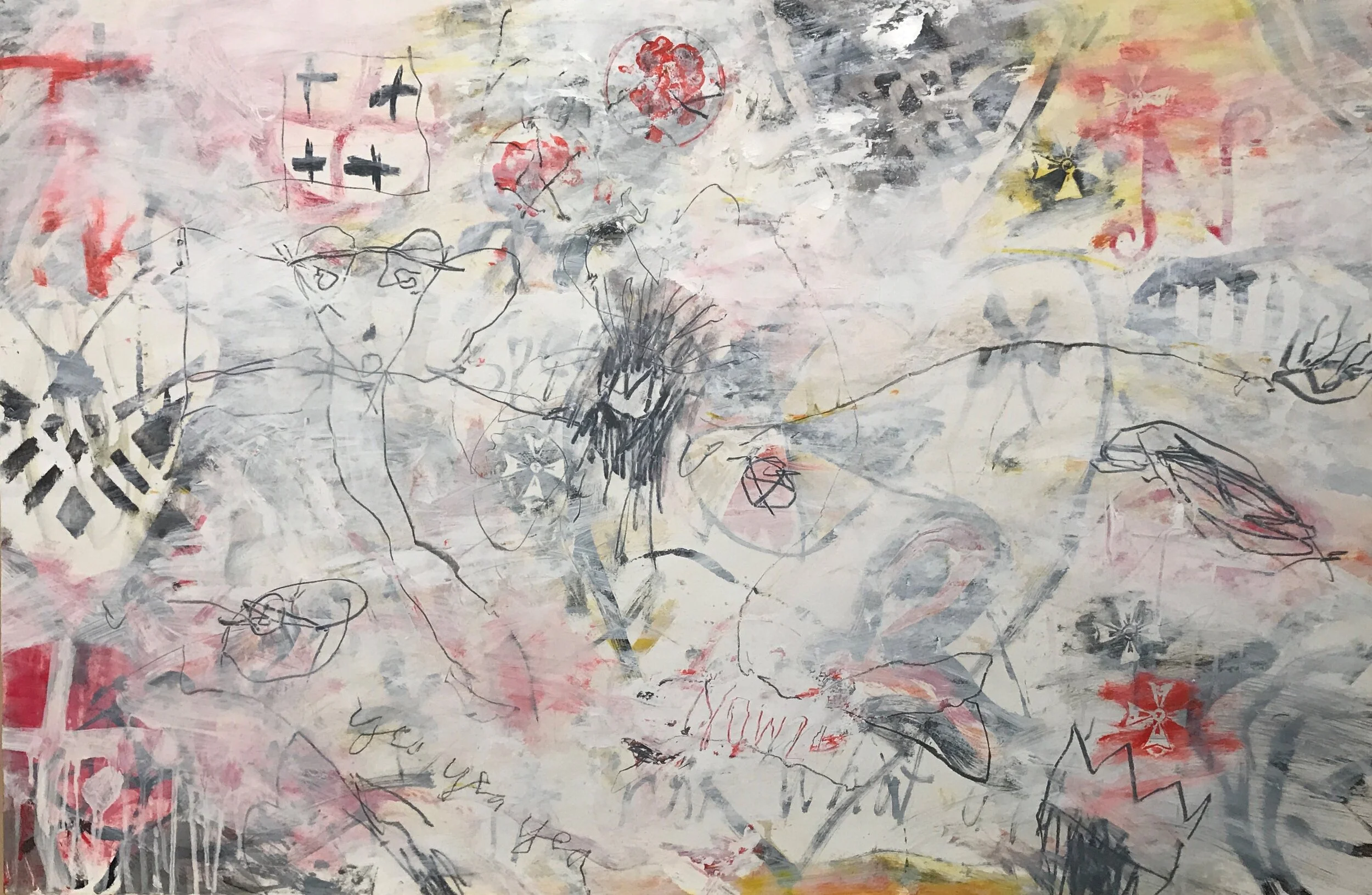

Ford Crull, Remembering You, 2017. Oil, oil stick and graphite on paper, 26.5 by 40 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

A resonance of the mystical 1920 Angelus Novus (New Angel) of Paul Klee—first purchased by Walter Benjamin in 1921 and presently in the collection of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem—can be seen on the left side of the composition of Remembering You (2017) of Crull. Here a primeval, heart-shaped face is drawn underneath four hastily-executed plus signs that are embedded within a Twomblyesque square, to the left of which the cursory letters T, P and V appear in red, seemingly liquefying, as if to insist that the written sign is first and foremost pigment before it takes on its value of a grapheme—the essential unit of the writing system. The figure of an insect, a dissolving cross, a floral motif and unintelligible forms are inscribed underneath the alphabetical characters and the heart-shaped face of Remembering You, where the accumulation of thin layers of paint gives way to a sense of nostalgia, of time and temporality, of individual and cultural memory.

Along with a figural and conceptual reference to Klee, this painting of Crull recalls the iconic crowns of Jean-Michel Basquiat: one within the center of the composition, amplified through electrifying lines, and one by the lower right hand edge, larger in scale. These two icons of crowns arrestingly convey a sense of intuitive perspective within the picture. In turn, the scribbled sign of the eye near the right edge of the painting translates as an uncanny confirmation of the possibility to assign such a concept of perspective to the painting, although mere rationality seems to be precisely what Crull’s artmaking rejects. Instead, the picture bespeaks pure open-endedness through his distinctive visual language. If fragments of text, symbols and icons are barely intelligible in Remembering You, there remains an exquisite interplay of coloration within the painting, as its predominantly light-gray and faint-pastel palette is accentuated with bright reds and yellows that are close to the boundaries of the picture surface. As such, this pictorial space of Crull sets a dialectic between figuration and abstraction, suggesting the necessity for both forms of expression within his vocabulary.

Ford Crull, Badge, 2004. Oil and wax on canvas, 60 by 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Another doppelgänger of Klee’s Angelus Novus predominates Badge (2004) of Crull. Executed through pugilistic fervor, this dark New Angel of Crull floats upon a lightly colored background containing abstract marks, numeric signs, alphabetical characters and hints of symbolic icons rendered through expressionistic scrimmages within a frenzied setting that is erratically framed by traces of pale teal, vivid ruby red, tangerine and Parrish blue.

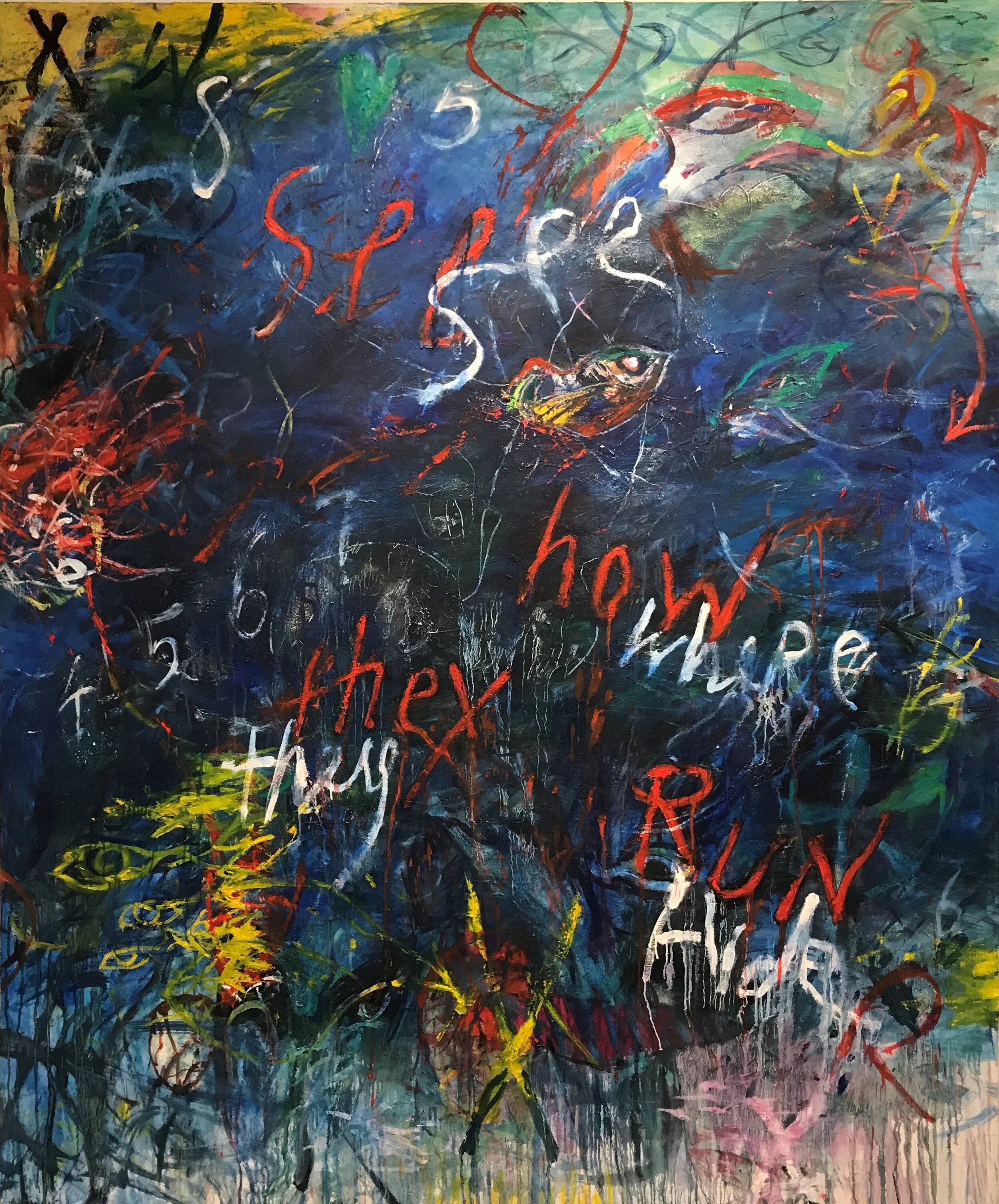

Badge is intriguing to behold through its signage and palette, as its principal motif not only reanimates Klee’s angel but the words of Walter Benjamin as well—insofar as despair is concerned within a given political climate or that of human history. Whereas the following words of Benjamin were directed at Klee’s spiritual motif from the viewpoint of the political instability within Europe that would ultimately lead to the author’s tragic suicide during World War II, they relevantly illuminate Badge of Crull, a painting executed nearly three years after the catastrophic collapse of the Twin Towers: “His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them.”[1]

As the studio of Crull is located nearly four blocks to the north-east of the World Trade Center, Badge comes across as a reiteration of Benjamin’s interpretation of Klee’s drawing: “This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”[2] This painting of Crull, who witnessed and went through the ravages of 9/11, conveys symbolic and emotional significance that is both autobiographical and historical.

Ford Crull, Templars, 2018. Oil, enamel, wax and graphite on canvas, 36 by 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Eliciting iconic absorption and dramatic introspection, the discursive elements of eye, heart and alphabetical letters recur in Templars (2018) of Crull, accompanied by the signage of arrows achieved through smears of fire engine red. Yet the surreal angel of Klee must have either flown away from the arena of Templars or become transubstantiated into a phantom that is left for the viewer to imaginatively assess—whether upon the visual field of Crull’s canvas or within the realm of one’s own mind.

In Midsummer Night, Ruby 2 (2010), the teal, ruby red, tangerine and Parrish blue of Badge become fused with shades of yellow and viridian green, inhabiting a space no longer predominated by light greys but instead framed through the emblems of the heart and arrowed cross that are rendered primarily in black. Here Crull imbues the work with an incandescent luminosity through a distinct painterly finesse, where the black foliage cross on the lower right side of the picture surface appears vibrantly back-lit through shades of green, blue and orange. Luminescent forms command the dense composition of Midsummer Night, Ruby 2, a painting inhabited by icons, alphanumeric symbols and haptic marks rendered through the artist’s hand, visible in the middle left section of the composition.

Ford Crull, Midsummer Night, Ruby 2, 2010. Oil, oil stick and enamel on canvas, 60 by 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Resplendent with exuberant coloration, the diptych titled Doublecross (2015), measuring forty inches high and sixty inches wide, renders the foliage cross as a central figure of each panel. Vibrant colors and expressive brushstrokes formulate the imagery of these two panels, whereupon the semiotic vocabulary of Crull is palpable, although gestural strokes have overtaken the icons and symbols to a substantial extent. The chromatic dynamism of Doublecross brings together the relatively understated aesthetic of Remembering You and the vibrant palette of Midsummer Night, Ruby 2.

Ford Crull, See How They Run, See How They Hide, 2018. Oil, oil stick and wax on canvas, 72 by 60 inches.

Included in the exhibition are such thoroughly engaging paintings as Nothing You Said (2017), Many Rivers to Cross (2019) and Nothing Important (2019). These works often interweave the emblems of eye, face, head, heart, cross and alphanumeric symbols either centrally or repeatedly throughout a given pictorial surface, at times through gestural smears and smudges while at other times through orchestrated outlines of interconnected figures, such as in the remarkable triptych titled America 2 (2015), a multifarious work that epitomizes Crull’s gesturally executed pictograms. Revealing the canvas as a showground of the simultaneity of organization and experimentation, of regulation and liberty, of austere symbolism and expressive exuberance, these intriguing works of Crull evoke the existential quest of the individual.

Ford Crull, New Star 2, 2019. Oil and wax on canvas, 48 by 36 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Within the painterly parlance of Crull, chance at first appears as having separated the work from the ego of the artist, whose artmaking demonstrates an insistence to transcend verbal definitions of subject and style—neither having recourse to the purely abstract nor that of sole figuration. As such, a given painting presents a visual space caught between the atmospheric and flat, between the elusive and referential, between opticality and materiality, between artmaking and reality. That illusive space consists of an accumulation of painterly coatings, gestural marks and cultural codes open for interpretation through the spectator’s imaginary realm.

Yet these works also remain inevitably framed through the historical context of the Tribeca district of Manhattan at the outset of the twenty-first century. As the emblematic and highly painterly devices within a painting of Crull often interweave and dissolve, the enigmatic image is transformed into an allegorical landscape of what culture has come to designate as the unconscious—at once personal, collective, aesthetic, cultural and historical. The eye is tempted to slide endlessly across surfaces covered in oil, enamel, oilstick, wax or graphite, searching for a phantom of Klee’s and Benjamin’s New Angel whenever gazing at the evocative paintings of Ford Crull—whether it would be a pictorial or conceptual phantom.

Notes

Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (1940), in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt and trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), p. 257.

Benjamin, p. 258.