TO BEND THE EAR OF THE OUTER WORLD

Conversations on contemporary abstract painting

Gagosian | Grosvenor Hill, London and Davies Street, London

June 1 through August 25, 2023

Exhibition review by Raphy Sarkissian

To Bend the Ear of the Outer World, an engaging exhibition astutely curated by Gary Garrels, brings together abstract works by forty-one artists in Gagosian’s two Mayfair galleries. With its rhapsodic title lifted from Frank O’Hara’s 1956 free-verse poem “In Memory of My Feelings,” the exhibition extends the breadth of that poetry to abstraction’s own open-endedness in relation to visual codes and interpretations. What makes this project especially noteworthy is the accompanying catalogue in which a given reproduction of a painting is paired with text by the artist. These spreads of text and image within the catalogue evoke the Latin phrase ut pictura poesis or “as is painting so is poetry,” reframing abstraction so as its mythic autonomy and self-referentiality could become partly suspended, if not critically overturned. “I would like to abolish the terms abstract and figurative,” pleads Cecily Brown in her statement, concluding her thoughts by claiming that “Painting is closest to poetry of all the arts.”[1] The exhibition, subtitled Conversations on contemporary abstract painting, thus posits itself as a dialogical undertaking.

Left: Tomma Abts, Emko, 2023. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 18 7/8 by 15 9/16 inches. Right: Cecily Brown, It’s not yesterday anymore, 2022. Oil on linen, 67 by 123 inches. © Tomma Abts and © Cecily Brown. Photo: Lucy Dawkins. Courtesy of the artists and Gagosian.

It’s not yesterday anymore (2022) by Brown and Emko (2023) by Tomma Abts greet the visitor in the gallery’s Grosvenor Hill space. As the linear rigor of Abts is stylistically antithetical to the painterly bravura of Brown, the exhibition sets an absorbing dialectic between linearity and coloration, astoundingly recalling the discursive parameters of style as set forth by the art historian Heinrich Wölfflin. Throughout the exhibition, the debate between the draftsmanly and the coloristic lends itself as a recurring, resolved and perfectly unresolvable (if not dreamily paradoxical) formalist theme within a given painting. Running parallel with that dialectic, the concepts of opticality and tactility also come to one’s mind. “I sometimes think that my paintings feel more like objects or things,” writes Abts, reverberating art critic Clement Greenberg’s dichotomy between the disembodied, optical import of an abstract painting versus its embodied, tactile reality.

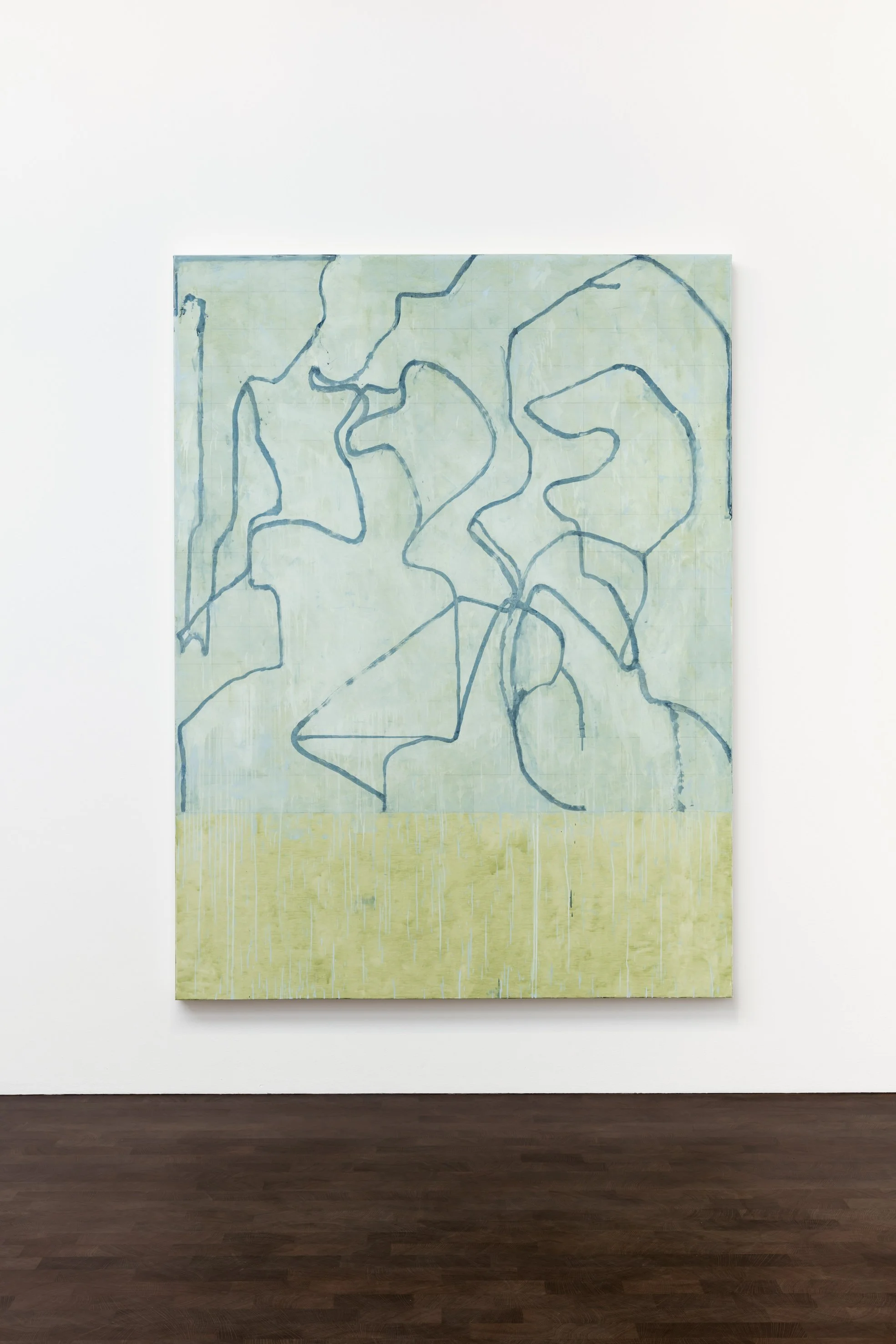

Brice Marden, Rivers, 2020-21. Oil and graphite on linen, 97 by 72 inches. © Brice Marden. Photo: Lucy Dawkins. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.

The dialectic between disegno and colorito, as set forth respectively by Abts and Brown, becomes expressively coalesced within the lyrical painting Rivers (2020-21) of the late great Brice Marden. Here meandering lines in shades of turquoise hover over successive veils of pistachio greens, staged above a broad rectangular field of shimmering chartreuse. Across the picture surface, interchanges between color and line poetically reverberate with those between figuration and abstraction. Marden has said, “If I want to paint water, I’m going to think of its reflections, its fluidity, its energy, its temperature, but not its appearance.”

Gerhard Richter, Abstraktes Bild (Abstract Painting) (952-1), 2017. Oil on canvas, 78 3/4 by 78 3/4 inches. © Gerhard Richter. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.

On an adjacent wall, in Gerhard Richter’s Abstraktes Bild (Abstract Painting) (952-1) (2017), colorito reaches an apotheosis through the artist’s quasi-mechanical method of deploying oil on canvas through the squeegee. “Illusion has never interested me,” contends Richter, adding that “Photography has almost no reality … And painting always has reality: you can touch the paint; it has presence; but it always yields a picture.” [Emphasis added.]

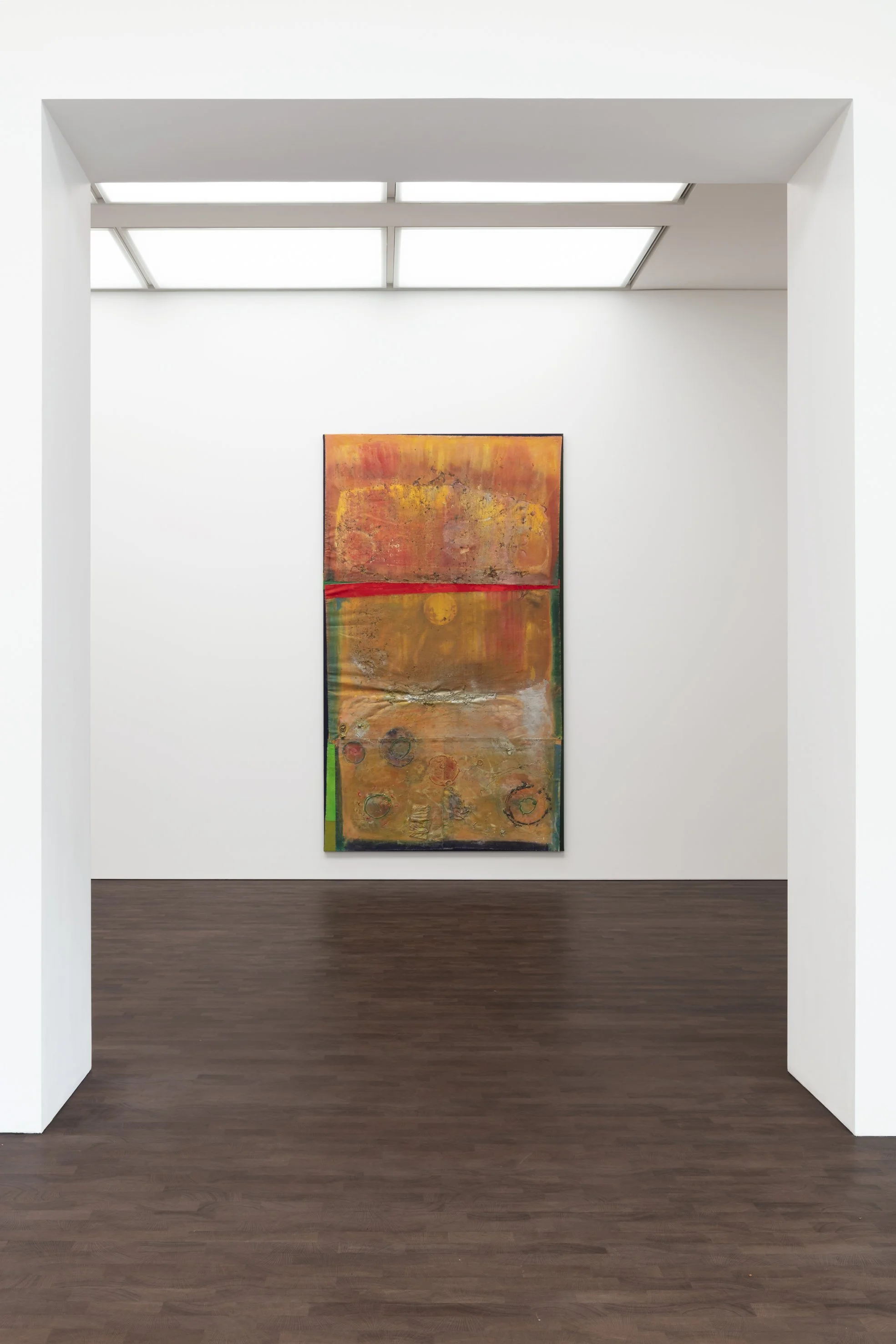

Having incorporated found objects as ghostlike entities within the mediums of acrylic and acrylic gel, Passtheball (2022) by Frank Bowling exudes polychromatic effulgence. The tangible and the spatial here register as inseparable phenomena. The tactile materiality of forms and mesmeric opticality of translucent films of color engross the observer within a hypnotic space. “I have always been frustrated about being pigeon-holed as a Black artist, and the expectations people have around what the work should look like and be about,” Bowling says. Accordingly, it is “the activity of painting itself” rather than sociopolitical concerns that has compelled Bowling to investigate the formalist pleasures of painterly abstraction in Passtheball.

Frank Bowling, Passtheball, 2022. Acrylic, acrylic gel and found objects on canvas with marouflage. 127 3/4 by 73 1/2 inches. © Frank Bowling. Photo: Lucy Dawkins. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.

Night Sky #22 (2015-18) of Vija Celmins enthralls the viewer through the illusiveness of luminous celestial bodies captured in enigmatic darkness. This finely crafted and sumptuous painting posits the all-too-familiar dilemma when abstraction and verisimilitude reveal themselves as the two sides of the same coin. “Inviting you in and keeping you out—both things at once,” discloses Celmins. Arresting the beholder at the cusp of cognitive awareness, the abstraction of Celmins gives way to the inference of illusion. “The surface is very closed and flat, but the feeling of the painting (I hope) is full and dense—like a chord of music,” reflects Celmins.

If Piet Mondrian, with his love of jazz, has come to epitomize the legacy of the Modernist grid that was established in 1917 by the Dutch art movement De Stijl in Leiden, that hallmark of abstraction continues to be transformed and reinvented: from the delicacy of Agnes Martin’s spartan grids to the symbolically coded structures of Peter Halley to the austere luminosity of Sean Scully. In this exhibition, Slow Walking (2022) of Stanley Whitney broadens the grid’s possibilities through its own distinctive voice. “Painting is like music,” claims Whitney. “When I first saw Cézanne, I thought, This is like Charlie Parker, only painting. It’s like polyrhythm, a beat and a beat and a beat and a beat.”

Left: Stanley Whitney, Slow Walking, 2022. Oil on linen, 72 by 72 inches. Right: Suzan Frecon, persian mare mars, 2022. Oil on linen, 108 by 87 3/8 inches. © Stanley Whitney, © Suzan Frecon. Photo: Lucy Dawkins. Courtesy of the artists and Gagosian.

A remarkable compositional feat and a benchmark of linearity, Suzan Frecon’s arresting painting titled persian mare mars (2022) evokes the subjects of architecture, landscape and nature, while remaining primarily nonrepresentational. Frecon explains, “Landscape, architecture, human beings, and their consciousness: it is all there, but it’s not a depiction.” Also addressing the simultaneity of the presence and absence of reference within abstraction, Mary Heilmann comments, “You compose music abstractly. You compose pieces of art in an abstract way too. … Every piece of abstract art that I make has a backstory. … Simple ideas become obsessions, almost like a meditation.” While the unconventional format of Heilmann’s two paintings touch on the concept of linearity in their own right, the thoroughly gestural application of riveting shades of emerald green in Deep Water (2022) and Dive Under (2022) has given way to evocations of underwater landscapes through high points of painterliness. By means of the dialectic of geometric linearity through the frame versus intense painterliness on the painting’s surface, Heilmann has expanded the possibilities of abstraction while carving a singular niche for herself upon the horizon of contemporary art.

David Reed, #593-3, 2005-09/2013-15/2019-22. Acrylic on polyester. 105 by 49 inches. © David Reed. Photo: Lucy Dawkins. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.

Painterly gestures in purple dance extemporaneously atop the linearity of vertical stripes in shades of pink and red in David Reed’s captivating #593-3, executed intermittently between 2005 and 2022. The inquiry into the polarities of color and design reaches one of its utmost heights here. “I think of color first. I think color is the most important aspect of a painting now,” reflects Reed. In turn, such a formalist and conceptual dialogue takes on its own distinct course within the extraordinary pictorial language and words of Pat Steir. The tripartite composition of Rainbow Waterfall #6 (2022) exhibits sheer painterliness. Steir eloquently describes her creative process by noting that “the painting paints itself during the night. I like that, because I relinquish responsibility. I can enjoy my work because I believe it makes itself.” The poetic waterfalls of Steir, in rose taupe, yellow and green, set on an orange ground, virtually conceal the perceptual distinctions between the reality of the world and the medium of painting, between resemblance and abstraction, between gravity and its absence.

Dark, Delphic and immense in scale, Untitled (2019) of David Hammons is a staggering high point of the exhibition, as it transgresses the cultural logic of abstraction. A black, diaphanous drapery obscures a vibrantly colored Abex painting that brings to mind such legendary names as Willem de Kooning and Clyfford Still, along with those of contemporary practitioners of gestural abstraction. Shades of color in art, shades of color of skin, cultural identity, degrees of visibility, degrees of obscurity: conveying such intimations to the observer, Hammons invites us to interrogate the role of abstract painting within the contexts of the historical and sociocultural. “I feel that my art relates to my total environment—my being black, political, and social human being,” explains Hammons. Translucent plastic, itself enshrouding the black drapery, uncannily unfolds limitless shades of gray, rendering the whiteness of the wall and blackness of the veil as chromatic boundaries if not reductive social identities. “Although I am involved with communicating with others, I believe that my art itself is really my statement. For me, it has to be,” insists Hammons.

David Hammons, Untitled, 2019. Mixed media. 159 by 137 by 12 inches. © David Hammons. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.

Unabashed painterliness, chromatic bravado and gestural liberty predominate the two southeast spaces of the gallery’s ground floor, although the dynamics of line and design continues shifting within a given work. Paradoxically, the emotive power and Wagnerian “gestures” of Wade Guyton are technologically generated on linen. Also derived from digital printing, MN+//sss (2023) by Jacqueline Humphries imparts an illusory gestural elegance that becomes capriciously metamorphosed into digital characters as the onlooker proceeds toward the picture surface to observe the painting proximately. In The Garden of Earthly Delights (2021) by Mary Weatherford, painterliness reaches one of its paramount heights. Titled after the masterpiece of Hieronymus Bosch and seeming to refer to the uppermost scene of the The Hell panel of Bosch, the unrestrained expression of color and gesture of Weatherford’s painting brings to mind the compositional dynamism and chromatic vitality of Eugène Delacroix’s Death of Sardanapalus (1827) at the Louvre.

Charline von Heyl, Circus, 2022. Oil, acrylic and charcoal on canvas. 82 by 78 inches. © Charline voy Helyl. Photo: Lucy Dawkins. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.

Though interchanges between linearity and painterliness are shaped entirely differently within a given work on view, such conversations among the paintings hanging next to or across from one another amplify aesthetic exchanges. The highly subjectivist and achingly beautiful coloristic works of Christopher Wool, Albert Oehlen, Richard Aldrich, Suzanne Jackson and Helen Marden embody pure and intense coloration. Albeit substantially painterly in style, linearity pronounces itself more audibly within the disarming abstractions of Laura Owens, Terry Winters, Amy Sillman and Tomm El-Saieh. Circus (2022) of Charline von Heyl superbly lays bare the polarities of linearity and painterliness. “It is terribly difficult to write about painting, especially abstract painting,” confesses von Heyl. “It’s a slippery entity that’s hard to catch with words because in its essence it doesn’t want to be described. That’s actually a great challenge, and I love to invite people to the chase,” von Heyl ruminates.

Oscar Murillo, manifestations, 2020-22. Oil, oil stick, graphite and spray paint on canvas and linen. 110 1/4 by 106 1/4 inches. © Oscar Murillo. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.

Emitting visceral energy through its rhythmic indexical marks of oil and oil stick in intoxicating coloration, Oscar Murillo’s manifestation (2020-22), hanging on the upper floor of the Grosvenor Hill gallery, captures the spectator with its own definition of realism: “I endeavor to strive for a sense of authenticity…. Dirt is real and is everywhere; it is accessible whether in the streets of London or in the villages of Columbia, dirt is democratic and free, so a dirty canvas is an extension or a reality even if you romanticize it,” insists Murillo. Predominated with hypnotizing shades of blues, turquoises, greens and teals, Jadé Fadojutimi’s ravishing landscape painting And willingly imprinting the memory of my mistakes (2023) is a chromatic tour de force of the exhibition. Touches of bright orange and pink in the forms of floral and vegetal motifs run across the painting’s surface, punctuating the extraordinary coloration of the canvas with sensualities that enchantingly dissolve the divisions of the terrestrial and aquatic. It is as if Fadojutimi has captured a given moment of the phenomenological process of visual perception whereby light, photoreceptors and electrical signals traverse from the retina to the brain by means of the optic nerve.

Jadé Fadojutimi, And willingly imprinting the memory of my mistakes, 2023. Acrylic, oil, oil pastel and oil bar on canvas, 118 1/8 by 196 7/8 inches. © Jadé Fadojutimi. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.

As opposed to the coloristic works that prevail the show, Nathlie Provosty’s diptych titled Clepsydra (2023) stands out through the marked linearity of its geometric motifs. With its title denoting an hour clock, a timepiece that connotes history, Provosty’s pictorial language reveals classical techniques of illusionistic representation. Having modeled concentric circles and discs so as to propagate perceptions of protruding and receding architectonic forms, the geometric abstraction of Provosty comes across as an amendment of the historical gap that seems to have halted the techniques of chiaroscuro and tenebrism over the course of abstract art’s dissemination. An unmistakable reminder of color as the existential condition of line, a cluster of Provosty’s gestural strokes in captivating shades of midnight blue gazes at us from the upper left corner of Clepsydra. Thilo Heinzmann addresses the ontology of painting through the materiality of oil, pigment and glass on canvas, noting that a given painting has “a life of its own, but at the same time” paintings “can become our conversational partners.” In Tauba Auerbach’s painting Grain–Standing Mandelbrot Quartet (Ventrella Variation) (2022), a flame-shaped image is suspended diagonally across the bare picture surface, evoking abstraction’s vigor, transience and omnipresence. “For me the divine is everywhere,” says Auerbach, “from the amazing architecture of something like a shell, to things like dark matter, the bending of space-time, and whatever consciousness is.” Whereas John Zurier’s monochromatic Love Letter (2022) brings coloration to yet another height through Cézannian rhythms, Triple Bold Bar, End Measure (2022) of Jenni C. Jones epitomizes linearity. For Ryan Sullivan process and gesture lead abstraction to “somewhere unpredictable,” to somewhere aesthetically irresistible.

Katharina Grosse, Untitled, 2022. Acrylic on canvas, 93 ¾ by 62 ¼ inches. © Katharina Grosse. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.

The potent dialogue between disegno and colorito within abstraction reaches further crescendos within Gagosian gallery on Davies Street. Each of the four paintings in the front space addresses the dichotomy of linearity and painterliness in its own distinctive manner. Within the paintings of Katharina Grosse, neon colors applied obliquely through spray gun radiate pulsating expressiveness. Chromatic Light Paintings (panoptes) (2022) of Julie Mehretu immerses the observer within a hallucinatory pictorial space where gestural mark-making and linear precision register as virtually one and the same. Ablaze in smudges of bright oranges, variations of carmine, flashes of yellows and shades of teal blue, Cloud Across a Sunny Field (2023) of Mark Bradford comes across as a chromatic detonation. Addressing abstraction’s significance in relation to its social context, Bradford claims, “I didn’t want abstraction that was inward looking; I wanted abstraction that looked out at the social and political landscape. … If power is abstraction, which many Black men, Black women, and people of color have very little voice in, well, then I want to sit at that table.” Also exuding a mesmerizing sense of chromatic vitality and viscerality, Mark Grotjahn’s Untitled (Backcountry 94.99) (2023) engulfs the viewer through its rhythmic impasto lines and bands. Grotjahn has distinctively reconfigured relational possibilities of linearity and painterliness.

Lesley Vance, Untitled, 2023. Oil on linen, 80 by 67 inches. © Lesley Vance. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.

Three of the abstractions in the back space of the gallery on Davies Street firmly convey the quintessence of colorito, often dissipating the distinctions between figure and ground. Here the paintings of Pamela Helena Wilson, Richard Hoblock and Matt Connors bathe the eye with chromatic pleasure and voluptuous radiancy. The serpentine bands of Untitled (2023) of Lesley Vance, on the other hand, propose a highly linear and mannerist syntax that is astonishingly inclusive of painterliness through its own modus operandi: here color and line remain entirely distinct from each other; there they wholly dissolve into each other.

As if an abstracted precis of Wölfflin’s phenomenological examination of style, this exhibition comes forth as a crystallization of the incisive thoughts of the art historian. “The great opposition between the linear and painterly styles corresponds to a fundamentally different interest in the world,” explains Wölfflin. That difference harks back to painting’s idealized representation of the rationally perceived world during the Renaissance period, as opposed to the selective representation of visual perception during the Baroque period. Referring respectively to the Renaissance and Baroque styles, Wölfflin strikingly differentiates the corporeality of objects within the world from the incorporeality of our visual perception of them: “In the former it is the fixed shape, in the latter the changing appearance … perception now pushes on beyond the tangible object into the realm of the intangible: it is only with the painterly style that noncorporeal beauty is recognized.”[2] While abstraction’s nonrepresentational essence may disconnect it from both tangible objects and intangible imagery that are identifiable, Abts has reinvented the linearity of Mondrian and by extension that of Raphael. Contrarily, Brown has reinvented the painterly language of de Kooning and by extension that of Rubens. In eloquent dialogue with such a history of forms and functioning as an extrapolation of the boundlessness of form’s possibilities, the pink, green and white figures of Vance set against the yellow ground “bend the ear of the outer world” so as to continue generating legible and illegible, audible and inaudible, visible and invisible conversations on contemporary abstract painting.

Notes

1. Gary Garrels, ed., To Bend the Ear of the Outer World: Conversations on contemporary abstract painting (Uckfield, England: Gagosian and Pureprint Group, 2023), exhibition catalogue. This and all subsequent direct citations are taken from the statements of artists, as published in the exhibition catalogue.

2. Heinrich Wölfflin, Principles of Art History: The Problem of the Development of Style in Early Modern Art, trans. Jonathan Blower (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2015), p. 109.

Special thanks to Mr. Sean Scully and Mrs. Liliane Tomasko for their extraordinary support of the humanities and for their generous hospitality during my stay in London over the past two summers. Their encouragement of my pursuit of art criticism has been invaluable.