Joseph Kosuth Cunningly Inflects the Armenian Dictionary in Yellow Neon

Joseph Kosuth:

The Language of Equilibrium

Curated by Adelina Cüberyan von Fürstenberg

Venice, Italy

June 10 through

November 21, 2007

Exhibition Review | June 2007 | Raphy Sarkissian

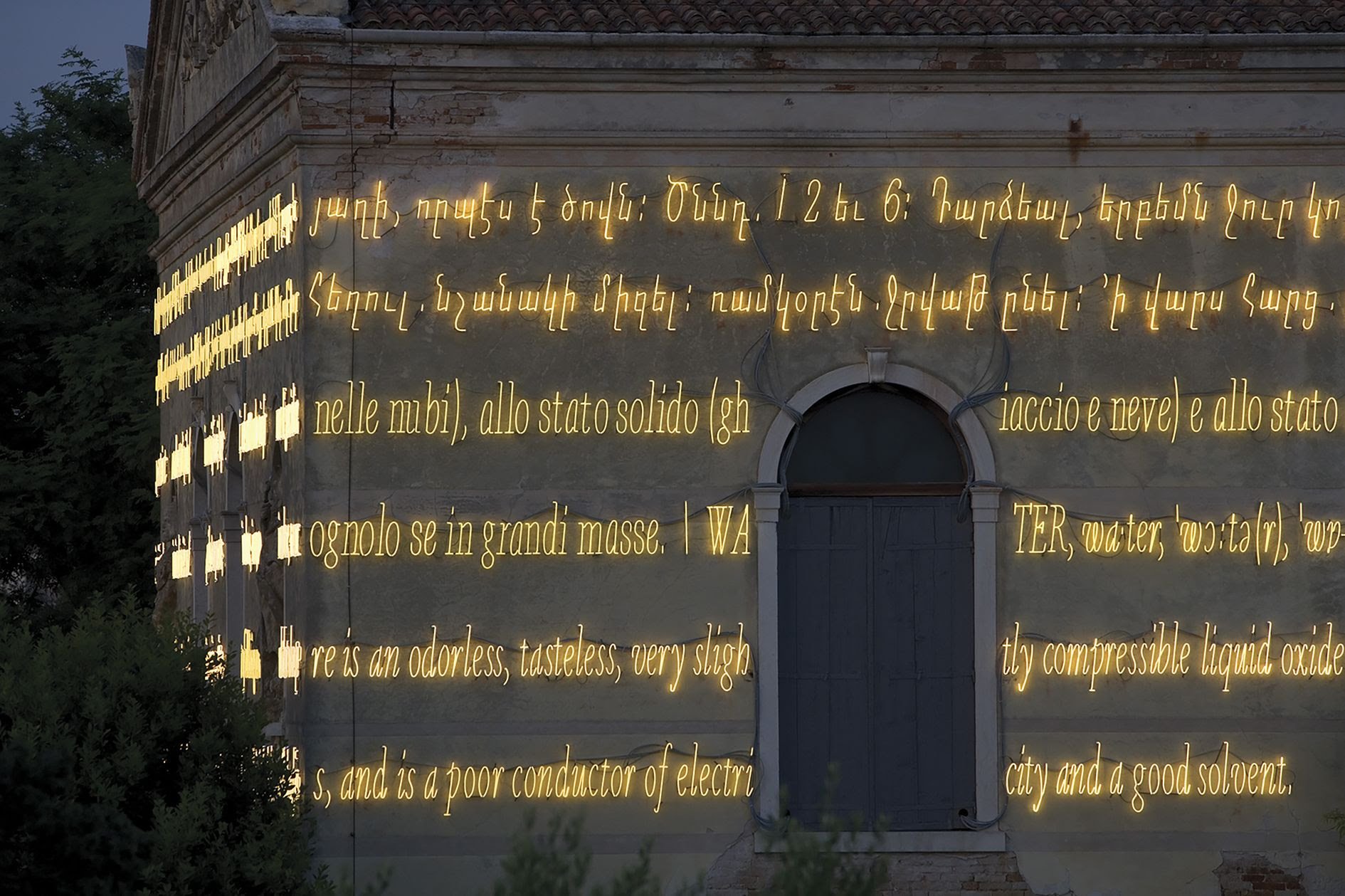

View of The Language of Equilibrium of Joseph Kosuth, Venice. Courtesy of the artist and ART for The World. Photo by Seamus Farrell.

If the name Arshile Gorky has become the indispensable and sole representation of Armenian culture upon the prominent landscape of the inescapably incomplete, official history of Western art, a minute yet remarkable expansion of that parable might be underway. This may in part be due to Joseph Kosuth’s groundbreaking project entitled The Language of Equilibrium that is currently on view in Venice, on the Island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni, at the Monastic Headquarters of the Mekhitarian Order.

This project, estimably curated by Adelina Cüberyan von Fürstenberg, founder of ART for The World, is a collateral event of the 52nd Venice Biennale that is organized for the first time by an American curator, Robert Storr.

Through audacious inscriptions of Armenian, Italian and English lexical terms and signs in yellow neon directly upon four diverse architectural surfaces, The Language of Equilibrium urgently rearticulates the visual and conceptual parameters of the locale and beyond, conjoining the far past and present. The promontory, the bell tower, the northwest wall and the observatory of the Monastic Headquarters are no longer solitary instances of architecture and urban setting. By means of a taut, graffiti-like undertaking, a secluded setting has become pertinently intruded by a sense of an obligation to narrate its own history and current state, which Kosuth has mapped to three languages.

View of The Language of Equilibrium of Joseph Kosuth, Venice. Courtesy of the artist and ART for The World. Photo by Seamus Farrell.

View of The Language of Equilibrium of Joseph Kosuth, Venice. Courtesy of the artist and ART for The World. Photo by Seamus Farrell.

Presently Professor at the Istituto Universitario di Architettura in Venice, Joseph Kosuth has based his installation on research of the color yellow and the word “water” within the context of the Mekhitarian Order. “Yellow neon,” Kosuth notes, “is chosen for this work because of the symbolic understanding of yellow at the time of the founding of the monastery as meaning ‘virtue, intellect, esteem, and majesty.’” In here, the definition of the word “water” has been extracted from the 1749 Armenian Dictionary, or Haygazian Pararan, compiled by Abbot Mekhitar of Sebastia.

Along with the lexical definition of the word “water” in Armenian, this simultaneously hyperobjective and sensuous textual opera juxtaposes dictionary definitions of the Italian counterpart “acqua” and the English word “water.” At first the viewer confronts the phonetics (pronunciation), etymology (root), syntax (grammar) and semantics (meaning) of water in three languages. Soon after, references to water are discursively invaded not only by physical water enveloping the island, but by water contained within the physical corpus of the viewer. Topography, mind and body are interwoven uncannily, evoking the range of conjectures put forth by the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein.

A journey to the Island of San Lazzaro thus becomes a journey to mind-body and text-image problems: Kosuth’s rendition of architectural surfaces through neon text as sites of verbal phenomena stems from an ingenious purport that obliges the visitor’s engagement within the archaeology of Armenian culture and its history, a culture that is simultaneously autonomous and tied to other cultures—past and present.

View of The Language of Equilibrium of Joseph Kosuth, Venice. Courtesy of the artist and ART for The World. Photo by Seamus Farrell.

Modernism had infused painting with linguistic signs and words through Cubism (Picasso) and Surrealism (Magritte), among other movements, leading on the one hand to the expansion of painting as at once a verbal and visual phenomenon, while on the other hand paradoxically isolating painting by committing it to pure abstraction via the primacy of line (Mondrian, Malevich) and that of color (Gorky, Pollock). The autonomy of painting would culminate in the Minimalist “Specific Objects” of Donald Judd, who had reduced the boundaries between painting and sculpture by 1963. In the mid-sixties, however, “it was Joseph Kosuth who quickly saw that the correct term for this paradoxical outcome of modernist reduction was not specific but general,” as art historian Rosalind Krauss discursively notes. “That’s because the word art is general and the word painting is specific,” states Kosuth.[1] For Kosuth, one can say, art, language and philosophy are inseparable on one level or another.

Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Chairs, 1965. Wood folding chair, mounted photograph of a chair, and mounted photographic enlargement of the dictionary definition of "chair." Chair 32 3/8 by 14 7/8 by 20 7/8 inches, photographic panel 36 by 24 1/8 inches, text panel 24 by 30 inches. Larry Aldrich Foundation Fund. Copyright © 2019 Joseph Kosuth / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist, Sean Kelly Gallery and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

It is somewhat impossible to disconnect The Language of Equilibrium from Kosuth’s 1965 paradigm of Conceptual art, an artwork entitled One and Three Chairs, in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. By placing a photograph of a chair next to the physical chair, itself next to a dictionary definition of the word “chair,” Kosuth has submitted the definition of art to a theoretical and essentialist revision. Namely, before semiotics and structuralism would become spread and methodologically utilized in art, criticism and history, Kosuth had conjugated signification itself through three intersecting devices: the Duchampian readymade, photography and language. The quagmire of the distinctions and inseparability of the object, the image, and the text is central to Kosuth’s schema.

View of The Language of Equilibrium of Joseph Kosuth, Venice. Courtesy of the artist and ART for The World. Photo by Seamus Farrell.

The Language of Equilibrium is not precisely a “comprehensive” work, for the moment the spectator diverts attention to the press release of the project, the neon text renders itself as somewhat of a surplus, now replaced by invaluable historical data available elsewhere. Nonetheless, Kosuth’s work acts as a key catalyst to text that is provided by the curator online: Abbot Mekhitar of Sebastia “settled together with his monks on the island in 1717 after escaping persecution. Mekhitar understood the implicit potential of the written word for the preservation of Armenian culture threatened by the vicissitudes of history. The monastery therefore not only has a rich library, consisting of over 140,000 volumes, but until 1993 it also contained an active printing office capable of publishing texts in thirty-six languages, making San Lazzaro a global reference point for Eastern and in particular Armenian culture. It is thanks to this printing office that the first translation of the Bible into Armenian was made, including a guide to grammar and a dictionary of classical Armenian. These books are archived in the library along with 4,500 precious manuscripts, including many illuminated works by Armenian miniaturists and by the Greek and Syrian holy fathers.” And today this online text desires to act as a catalyst to Armenian studies and beyond.

View of The Language of Equilibrium of Joseph Kosuth, Venice. Courtesy of the artist and ART for The World. Photo by Seamus Farrell.

As these luminous words impose themselves like veils upon architectural surfaces, the linguistic morphologies of Armenian, Italian and English serve as means of narrating material histories. But can unsteady histories ever gain equilibrium? Kosuth invites us viewers to delve into our languages resolutely so as to learn and perhaps unravel myths and truths through, upon and behind cultural veils, despite inevitable abysses all across. The acknowledgment of that inevitability is one crucial language of equilibrium.

At night, the optical purity of darkness renders space a backdrop for a rhapsodic transfiguration of Abbot Mekhitar of Sebastia. Yellow neon is Kosuth’s contingency of the Abbot’s lexicon now walking exuberantly on the water.

View of The Language of Equilibrium of Joseph Kosuth, Venice. Courtesy of the artist and ART for The World. Photo by Seamus Farrell.

Note

Rosalind Krauss, “A Voyage on the North Sea:” Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1999), p. 10.

Founder of ART for The World and recipient of the 2015 Golden Lion for the Best National Pavilion for the 56th Venice Biennale, Adelina Cüberyan von Fürstenberg is a leading international curator. Her visionary collaboration with such pioneering artists as Marina Abramovic, Anish Kapoor, Jannis Kounellis, Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Wilson has broadly expanded the context of art and significantly enriched its cultural values. The white wall of the gallery and the reality of the outside world have been commensurate within the curatorial practice of Adelina Cüberyan von Fürstenberg over the past four decades.