Liliane Tomasko: Shifting Shapes

Bechter Kastowsky Gallery

May 7 through July 6, 2024

Exhibition Review by Raphy Sarkissian

Liliane Tomasko, Shifting Shapes, installation view. © Liliane Tomasko. Photo: Robert Kastowsky. Courtesy the artist and Bechter Kastowsky Gallery, Vienna.

These most recent paintings of Liliane Tomasko present abstraction as a conduit for self-reflexivity. Upon color-drenched surfaces, raw traces of paint and concealed brushwork give rise to visual spaces wherein maelstroms of undulating bands and illuminated forms incite yet halt recognizable imagery. Painted wet-into-wet, free-floating marks give way to veiled and unstructured masses poised in space. Translucence and opacity meld into one another. Gesturally executed contours intertwine within unfathomable pictorial spaces, where form and formlessness restrain the gestalt. This suspension of the legibility of forms redirects the abstraction of the paintings from their self-containment to the ontology of visual perception, where figuration and abstraction coexist within sight, reveries, and dreams. Titled Shifting Shapes as a group, these hauntingly lyrical works of Tomasko caress the interstices of vision, echoing the thoughts of Maurice Merleau-Ponty: “‘Nature is on the inside,’ says Cézanne. Quality, light, color, depth, which are there before us, are there only because they awaken an echo in our body and because the body welcomes them.” [1] These paintings of Tomasko reveal themselves as windows to a primordial world that is in an interminable process of entering our awareness.

Liliane Tomasko, Shapeshifter (using gray to manifest dark violet), 2024. Acrylic and acrylic spray on linen, 60 by 55 inches. © Liliane Tomasko. Photo: Robert Kastowsky. Courtesy the artist and Bechter Kastowsky Gallery, Vienna.

Curved bands and accumulated layers of acrylic evoke choreographic movements of unidentifiable forms within an exterior world awash in light. Yet at the same time, Tomasko taps into the interior world of the body with her diaphanous brushmarks and spray-painted curls, recalling the mechanism of the mind and our sensory experiences. When shifting our attention from the external world to the internal realm of the body, Tomasko’s dynamic shapes and resplendent colors arrestingly register as correlates of visual perception, where chains of electrical signals are transmitted from the surface of the retina to the cerebral cortex through the optic nerve. These painterly explorations of Tomasko lure the onlooker to grasp those moments of awareness that instill vast gaps between semblance and abstraction, along with those moments of awareness when vision and abstraction manifest themselves as entwinements.

Liliane Tomasko, Shapeshifter (strolling through forgotten lands), 2024. Acrylic and acrylic spray on aluminum, 24 by 40 inches. © Liliane Tomasko. Photo: Robert Kastowsky. Courtesy the artist and Bechter Kastowsky Gallery, Vienna.

Representing neither incoming photons, nor retinal images, nor the brain’s neural tissue known as gray matter, these paintings of Tomasko nonetheless attach abstraction to the cerebrum, the somatic and the visceral. “From childhood the young Marcel was intrigued by how things are perceived, which is the domain of scientific optics and physics and not of aesthetics. How we see—a mental process—interested him at least as much if not more than what we see. This is one of the threads binding his works,” writes Barbara Rose regarding Marcel Duchamp’s artmaking process. [2] This interest of Duchamp in the mental process of visual perception runs parallel to the threads binding Tomasko’s process of picture-making. In 1999 Tomasko’s first representational painting of an unmade bed became a revelation of the inseparability of figuration and abstraction within visual perception. Referring to that painting Tomasko recalls, “To me it also represented a need to be connected to something that we don’t necessarily have direct access to. Of course, we have an innate need to understand, so light and clarity are a prerequisite. But I think we equally have a need to not understand, and I think that’s what, in a sense, my paintings are very much about—a desire to be connected to something that we can’t quite figure out.” [3] For Ludwig Wittgenstein, the limits of knowledge would become the limits of language. For Tomasko, the limits of knowledge appear and disappear through the paintwork on the picture surface and within the pictorial space.

Liliane Tomasko, Shapeshifter (yesterday and tomorrow, divided by the present), 2024. Acrylic and acrylic spray on aluminum, 24 by 40 inches. © Liliane Tomasko. Photo: Robert Kastowsky. Courtesy the artist and Bechter Kastowsky Gallery, Vienna.

This exhibition invites us to contemplate the relationship between our perception of the world and the mark-making process, between our phenomenological intuition and Tomasko’s painterly facture, where unsystematic renditions of form, gestural erasures, accidents, and traces of spontaneous movements of the hand, arm, and body give way to interstitial spaces of chromatic revelations. This current cycle is an addendum to Tomasko’s lifelong probing of perception and the thresholds of the visible world through a diverse repertoire of themes and mark-making processes. The shifts from firmly figurative representation of luminous spaces to semi-illusionistic paintings to the current nonfigurative imagery evoke the thoughts of Merleau-Ponty on the spatiality of one’s own body and motility:

The body is our general medium for having a world. Sometimes it is restricted to the actions necessary for the conservation of life, and accordingly it posits around us a biological world; at other times, elaborating upon these primary actions and moving from their literal to figurative meaning, it manifests through them a core of new significance: this is true of motor habits such as dancing. Sometimes, finally, the meaning aimed at cannot be achieved by the means of the body’s natural means; it must then build itself an instrument, and it projects thereby around itself a cultural world. At all levels it performs the same function which is to endow the instantaneous actions of spontaneity with ‘a little renewable action and independent existence.’ [4]

Within the last sentence of the foregoing citation, Merleau-Ponty borrows the phrase from Paul Valéry’s fascinating 1919 essay “Note and Digression” in which Valéry describes Leonardo da Vinci’s elaborate process of writing when the uomo universale is “at once the energy, the engineer, and the restraints.” Valéry’s sketch of Leonardo at work on his text vividly mirrors Tomasko’s driven process of painting: “One part of him is impulsion; another foresees, organizes, moderates, suppresses; a third part (logic and memory) maintains the conditions, preserves connections, and assures some fixity to the calculated design.” [5]

Liliane Tomasko, Shifting Shapes, installation view. © Liliane Tomasko. Photo: Robert Kastowsky. Courtesy the artist and Bechter Kastowsky Gallery, Vienna.

For Tomasko, to paint should mean to extemporize, as openly and fluidly as possible, a field of marks, scrawls, and colors “in which the released energy of the mind is used in overcoming real obstacles; hence the” painter “must be divided against” herself. “This is the only respect in which, strictly speaking, the whole” woman “acts as author. Everything else is not” hers “but belongs to a part of” her “that has escaped. Between the emotion or initial intention and its natural ending, which is disorder, vagueness, and forgetting—the destiny of all thinking—it is” her “task to introduce obstacles created by” herself, “so that, being interposed, they may struggle with the purely transitory nature of psychic phenomena to win a measure of renewable action, a share of independent existence.” [6] These words of Valéry on Leonardo, now adapted and rephrased, outline Tomasko’s nonlinear method of coalescing shapes and primordial intuition through agitated marks and luscious, arabesque-like traces of color.

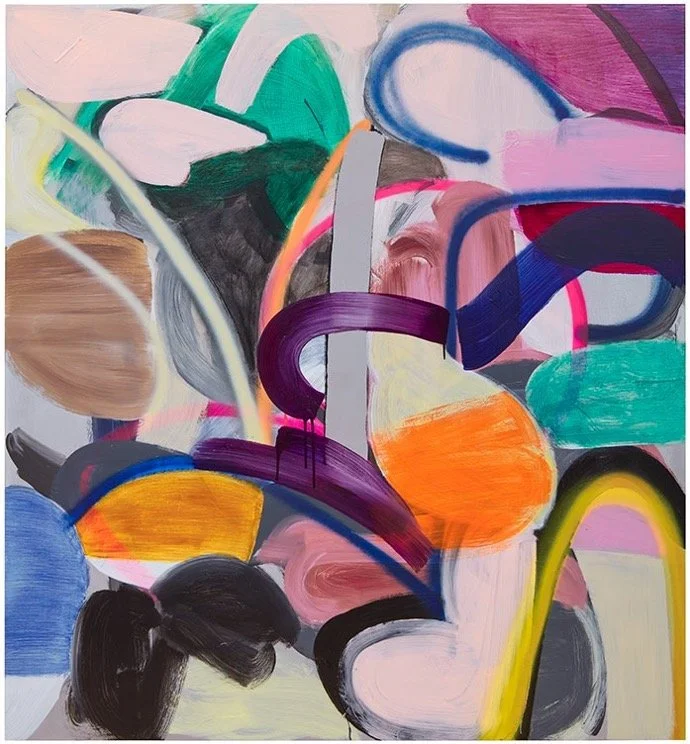

Liliane Tomasko, Shapeshifter (lost in a dream), 2024. Acrylic and acrylic spray on aluminum, 60 by 55 inches. © Liliane Tomasko. Photo: Robert Kastowsky. Courtesy the artist and Bechter Kastowsky Gallery, Vienna.

Predominated by muted shades of pink in conversation with vibrant and subdued colors, Tomasko’s medium-scale painting Shapeshifter (lost in a dream) displays opaque and sheer brushmarks that give rise to fragmented elliptical and spherical forms intermingled with winding bands. At times unmodulated and flat, at times wondrously illusory, serpentine stripes enact engaging counterparts of the brushstroke’s everchanging modalities. On the lower left, swirling strokes in dark shades of bluish-grey convey signs of chiaroscuro, a method that is reiterated in shades of cream and brown in the upper right corner of the pictorial space. Conversely, two opaque ribbons in taupe are displayed on the middle left and the upper right. Viridian billows extend vaporously from the upper left corner toward the center, overlapping ultramarine strokes that are partly concealed underneath a charcoal black curl. Whereas flowing blues and greens here conjure up chimerical landscapes, unbridled brushstrokes in pinks and greys give way to undertones of sensuous bodies in twirling motion. Strikingly, the painting comes across as an encapsulation of the endlessly shifting evanescence of dreams. As Tomasko has explained, “I am always trying to bridge the divide between sleep time and daytime, to establish a relationship between the two, and to bring them closer somehow.” [7]

Liliane Tomasko, Shapeshifter (emulating stability), 2024. Acrylic and acrylic spray on aluminum, 76 by 76 inches. © Liliane Tomasko. Photo: Robert Kastowsky. Courtesy the artist and Bechter Kastowsky Gallery, Vienna.

While Shapeshifter (emulating stability) is primarily nonfigurative, it imparts intimations of the visible world. In the upper right, an outdoor chair reveals itself, partially, in shades of olive green, acting as a window into an unknowable space behind. Throughout the painting, references to the scorching sun recur in shades of intense peach, bright red, glowing orange, and neon pink. In the upper center, a semicircular shape in riveting shades of blue suggests itself as a body of water. Calling to mind Vasily Kandinsky’s formative path toward abstraction through such a painting as the 1912 Improvisation 27 (Garden of Love II) of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Tomasko’s work regenerates Kandinsky’s pioneering vision. Closer to us in time, Albert Oehlen’s 1989 painting Untitled in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York comes forth as an exemplary counterpart to Tomasko’s poetic gestures that obliterate the divisions of mind and body, the visible and the invisible, the figurative and the abstract. Like innumerable practitioners of partial abstraction of our time (I am thinking of Rita Ackerman, Mark Bradford, Cecily Brown, Nigel Cooke, Julie Mehretu, and Amy Sillman to name only a few), Oehlen and Tomasko have embraced the medium of painting as a means of questioning the orthodox definitions of such semantic binaries as “linearity” versus “painterliness,” “gesture” versus “mark-making,” “drawing” versus “painting,” “form” versus “content.” In this manner, Tomasko’s visual project beckons the perceiving subject to reconsider and adjourn the unilateral definitions of “figuration” and “abstraction,” along with “hesitance” and “action.” Context cannot but relocate the significance of abstraction.

Liliane Tomasko, Shapeshifter (in a state of indecision), 2024. Acrylic and acrylic spray on aluminum, 76 by 76 inches. © Liliane Tomasko. Photo: Robert Kastowsky. Courtesy the artist and Bechter Kastowsky Gallery, Vienna.

An aggregation of vibrant outlines hovers within an irresolute space, where the landscape’s unboundedness and the body’s density are shaped through gossamer layers of color interlocked with shaded masses and opaque smears. In Tomasko’s Shapeshifter (in a state of indecision), the spatiality welled up by the layering of brushstrokes gives way to “a fragmented inscape of the psyche,” as described by Rosa Abbot. [9] For Merleau-Ponty the body is the primary place of knowledge, as he notes in his phenomenological approaches to reflection and interrogation: “What is given is not a massive and opaque world, or a universe of adequate thought; it is a reflection which turns back over the density of the world in order to clarify it, but which, coming second, reflects back to it only its own light.” [8] More abstract than Kandinsky’s 1913 Small Pleasures of the Guggenheim Museum, the overlaying shapes of Tomasko mediate vision through the space between the painting’s support and the observer’s retina. Recalling Arshile Gorky’s 1940 Water of the Flowery Mill of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the dense, opaque and translucent forms of Tomasko encapsulate primordiality through a phenomenological process that occurs within the studio of the painter.

Inside a given visual space of Tomasko, the “subjectivism” of gesturally generated forms and colors has been “consciously” or “unconsciously” negotiated with the “objectivism” of the historical presence of Kandinsky’s shift toward abstraction and Gorky’s tap on the elements of the psyche. The shifting shapes of Tomasko thus register as the ebb and flow between phenomenology and abstraction’s own history. Transforming paint into evocations of landscape, flesh, femininity, fluidity, masculinity, viscosity, and their in-betweens, Tomasko simultaneously transforms abstraction into a chorus of “conscious” or “unconscious” allusions punctuating the aesthetic horizon. These dreamscapes of Tomasko articulate the never-ending excavation of the painterly and perceptual processes, an excavation that can now be sustained by the spectator. Traces of the “instantaneous actions of spontaneity” within the chromatically rousing paintings of Liliane Tomasko recast the historic words of Luce Irigaray: “This abstraction which is not one.”

Notes

1. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “Eye and Mind,” in The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader: Philosophy and Painting, ed. Galen A. Johnson, trans. Michael B. Smith (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1993), p. 125.

2. Barbara Rose, “Rethinking Duchamp,” The Brooklyn Rail, December 14, 2014—January 15, 2015.

3. Liliane Tomasko, in Liliane Tomasko: Dark Goes Lightly (London: Bookworks, 2019), n.p.

4. Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (1962; London: Routledge, 1995), p. 146.

5. Paul Valéry, “Notes and Digression,” in Leonardo Poe Mallarmé, trans. Malcolm Cowley and James R. Lawler (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1972), p. 72.

6. Valéry, ibid.

7. Tomasko, ibid.

8. Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, trans. Alphonso Lingis (1968; Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1995), p. 35.

9. Rosa Abbott, “You Want It Darker,” in Liliane Tomasko: Dark Goes Lightly, n.p.

“For Tomasko, the limits of knowledge appear and disappear through the paintwork on the picture surface and within the pictorial space.”

Liliane Tomasko, Shapeshifter (in a state of indecision), 2024. Acrylic and acrylic spray on aluminum, 76 by 76 inches. © Liliane Tomasko. Photo: Robert Kastowsky. Courtesy the artist and Bechter Kastowsky Gallery, Vienna.

Vasily Kandinsky, Small Pleasures, 1913. Oil on canvas, 43 1/2 by 47 1/4 inches. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Arshile Gorky, Water of the Flowery Mill, 1944. Oil on canvas, 42 1/4 by 48 3/4 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.