Richard Hearns:

Autonomous

Yet Referential

Richard Hearns carrying Tome (2021) at the Burren National Park, County Clare, Ireland, 2021. Photograph by Eoin Collins. Courtesy of the artist and Cadogan Contemporary, London.

Richard Hearns: Enclave | Cadogan Contemporary, London | June 8 through 25, 2021 | Essay by Raphy Sarkissian

I make sense of paint. I journey with it. I live through the medium. For me there is sort of a salvation that exists in the act of painting. —Richard Hearns

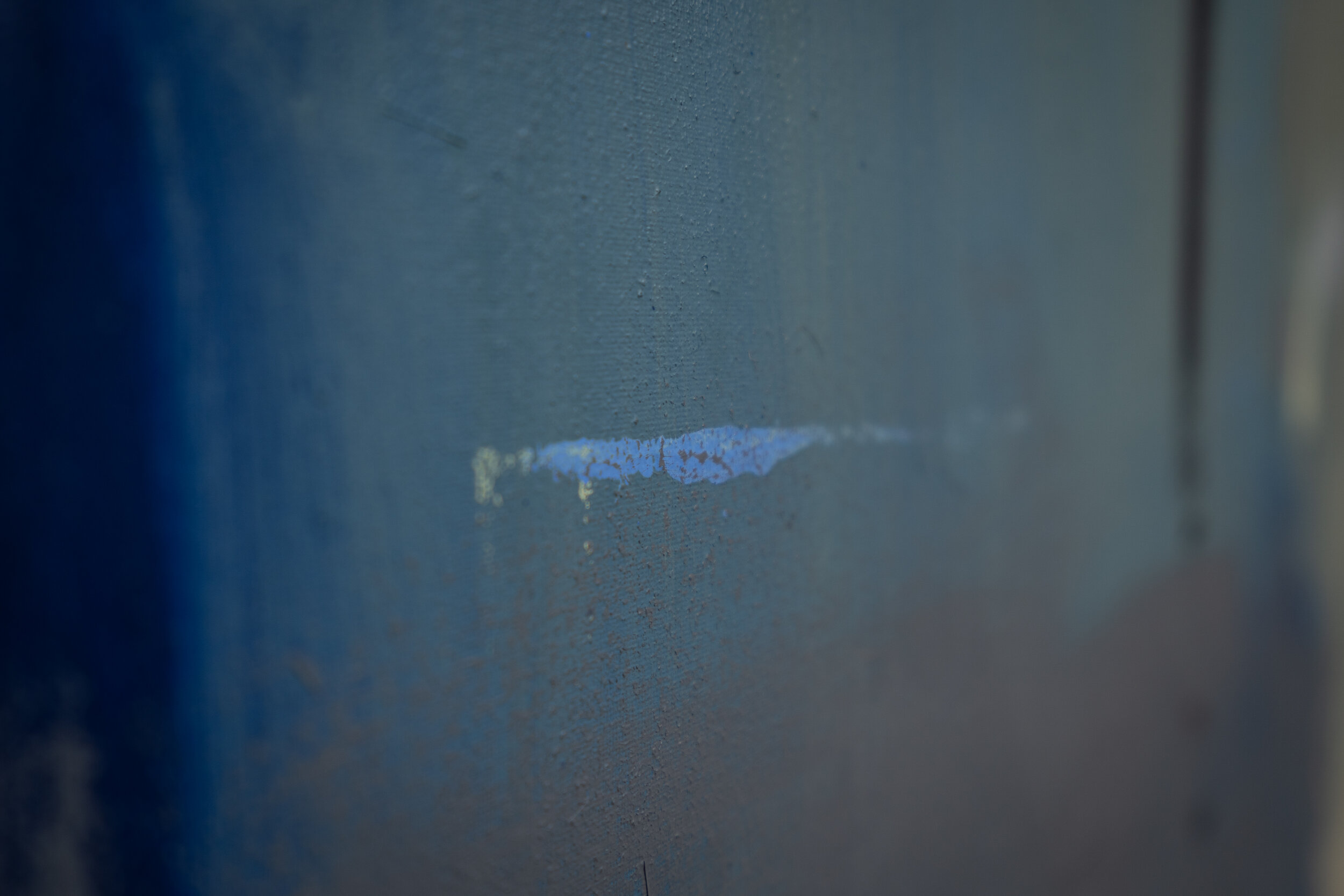

Executed through a highly gestural syntax, Keystone of Richard Hearns captivates the viewer through a hazy luminosity induced by its electrifying tints and shades of blue smeared upon, lying beneath and skirting the white, black and grey brushstrokes. As the painting displays a set of interchanges between forms of abstraction and vaguely decipherable pictorial references, the materiality of oil paint evokes the opticality of bodies of water, land, mist and sky. Glowing and dim, dense and sparse, substantive and imperceptible, Keystone comes across as autonomous and referential at once.

Richard Hearns, Keystone, 2020. Oil on canvas, 178 by 132 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Cadogan Contemporary, London.

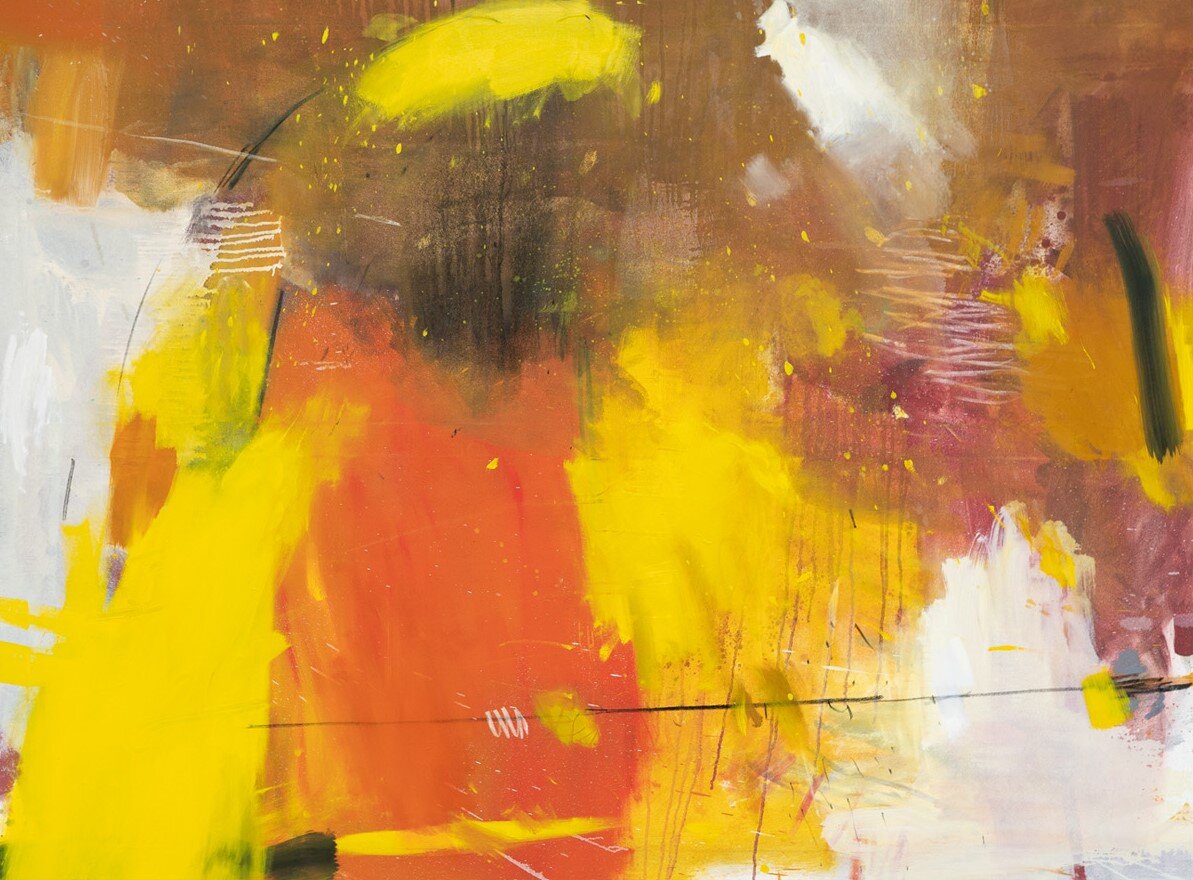

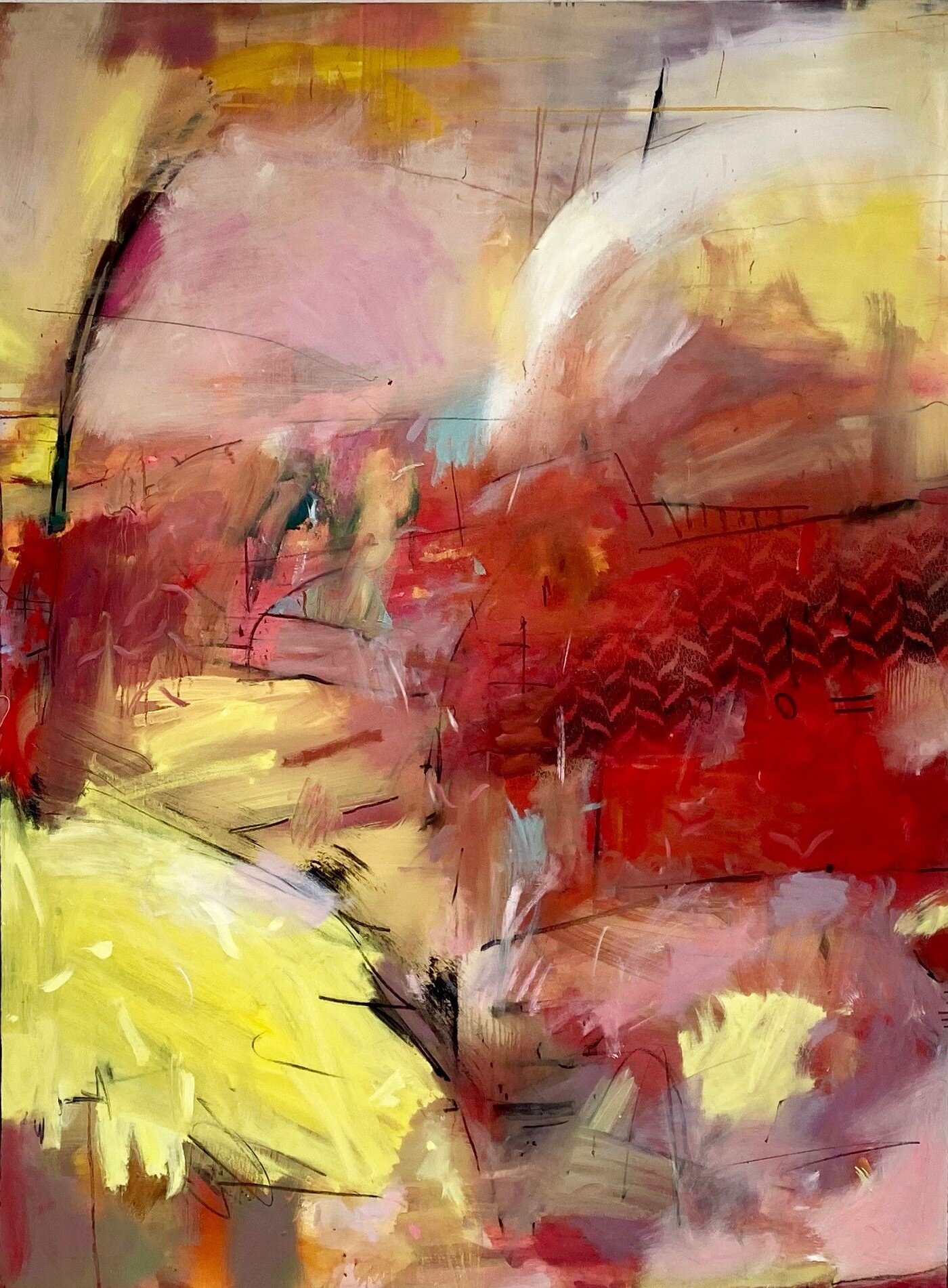

Enigmatically titled through such architectural terms as voussoir, keystone, intrados and extrados, the paintings of the recently executed suite Enclave exuberate opulent color palettes through painterly bravura and chromatic undulations of planarity and recession, flatness and space. Demonstrating the artist’s distinct command of raw mark-making that drives the composition to the threshold of the landscape, Enclave can be read as an exceptional tribute to the legacy of Abstract Expressionism, a term used by Alfred H. Barr Jr. in 1929 to characterize the non-representational paintings of Vasily Kandinsky. While these paintings by Hearns recall the visual syntax of such modernist masters as Arshile Gorky due to their sweeping drips, Franz Kline due to their gestural bravura, and Mark Rothko due to their blurred edges, it is perhaps a number of paintings by Willem de Kooning executed in the late fifties through 1960 with which the recent works of Hearns conjure up the most powerful aesthetic interactions.

Richard Hearns, Camber, 2021. Oil on canvas, 178 by 132 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Cadogan Contemporary, London.

Action Painting, the term coined by the art critic Harold Rosenberg in 1953 to characterize the immediacy of the painter’s handling of the brush to produce gestural traces upon the surface of the canvas, remains inseparable from our interpretation of the paintings of the Enclave series. In his pivotal article “The American Action Painters,” Rosenberg notes, “The painter no longer approached his easel with an image in his mind; he went up to it with material in his hand to do something to that other piece of material in front of him. The image would be the result of this encounter. … Art as action rests on the enormous assumption that the artist accepts as real only that which he is in the process of creating.”[1] Rosenberg’s emphasis on the process of painting as an end in itself sheds light on the aesthetic directions of such modernist painters as Gorky, Kline, Rothko and de Kooning. Having assimilated formalist elements from the visual syntax of these modernist masters with supreme fluency, Hearns expands the potentialities of Abstract Expressionism. With its pictorial allusiveness to the landscape genre, barely decipherable phantoms of architectonic forms, colored materiality and recurrent architectural titles, the distinct pictorial language of Hearns redefines and reinvents the expressive possibilities of the medium of oil on canvas through its singular set of parameters. This preoccupation of the artist with pairing nature and architecture abstractly and linguistically reactivates the historical and phenomenological questions posed by Filippo Brunelleschi’s so-called scientific perspective. While Hearns “registers,” “records” and “marks” his observations of the atmospheric fluctuations within nature and upon architectural surfaces and forms, he also “registers,” “records” and “marks” his observations of painting’s own historical and conceptual fluctuations.

The thoroughly painterly and seemingly nonmimetic features of Keystone remind us of the visible brushwork and blurred, soft edges of Rothko’s translucent painting Untitled (1948), while the palette of Keystone evokes the luminous Blue and Gray (1962) of Rothko, both at the Fondation Beyeler in Riehen, Switzerland. With its dynamism of bold strokes of paint, Keystone also initiates a compelling dialogue with Meryon (1960-61) of Kline at the Tate, as both paintings majestically celebrate the highly subjective language of abstraction through impulsive sweeps of paint. In turn, the flowing drips within Keystone are reminiscent of a number of paintings by Gorky, such as How My Mother’s Embroidered Apron Unfolds in My Life (1944) of the Seattle Art Museum in Washington. Though Gorky’s painting displays biomorphic forms through transparencies of colors and the dissolution of contours into drips, the sweeping strokes and drips of Keystone appear atop, behind and in between one another, exhibiting the sheer materiality of the textured surface and evoking an utterly dreamy, atmospheric realm.

Richard Hearns, Vestige, 2017-2021. Oil on canvas, 178 by 132 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Cadogan Contemporary, London.

With their elusive compositions, sweeping brushstrokes, dribbles and splatters, such gesturally executed paintings of Hearns as Tome, Corbel, Extrados and Camber call to mind a set of monumental paintings by de Kooning, including Montauk Highway (1958) of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Merritt Parkway (1959) of the Detroit Institute of Arts, A Tree at Naples (1950) of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Villa Borghese (1960) at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Door to the River (1960) at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In the paintings of both de Kooning and Hearns, abstraction often remains in dialogue with the landscape genre through compositional elements, chromatic implications or titles. These paintings by both artists reveal instances of pictorial shallowness, self-referentiality and autonomy, despite their paradoxical allusions to spatiality, natural settings, suburban localities, the countryside, distant views, open spaces or architectonic forms.

The intriguingly formulated visual grammar of Hearns can thus be read as founded upon innumerable instances of modernist abstraction, with the exuberant gesture as a decisive means of improvisation. Floating upon the picture surface of Keystone we witness interactions among shades of cream, grey, Argentinian blue, Celtic blue, Spanish blue, Delft blue and sapphire. A symphony of blues orchestrated upon the canvas that measures just under six by four-and-a-half feet, the scale of the painting resonates with the artist’s physicality, conceptually recalling Leonardo da Vinci’s ink-on-paper drawing Vitruvian Man of around 1490 at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice. Through the extension of the human figure’s four outstretched limbs so as to establish correlations between the body, circle and rectangle, Vitruvian Man maps the human body to architecture, the anthropometric to the geometric, the real to the ideal.

Richard Hearns, Voussoir, 2020. Oil on canvas, 132 by 178 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Cadogan Contemporary, London.

Yet within the paintings of the Enclave series, architectonic forms virtually dissolve into fields of formlessness. Through their chromatic exuberance and materiality or thingness (dinghaftigkeit) of paint, the highly gestural abstractions of Hearns recall the concept of the “abstract sublime.” In his influential article “The Abstract Sublime,” published in 1961 in Art News, Robert Rosenblum interpreted paintings by Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman through the concept of the sublime initially formulated by Edmund Burke in his treatise A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, published in 1757. In his discussion of Rothko’s painterly vernacular Rosenblum explains,

In his Critique of Judgment (1790), Kant tells us that whereas “the Beautiful in nature is connected with the form of the object, which consists in having boundaries, the Sublime is to be found in a formless object, so far as in it, or by occasion of it, boundlessness is represented.” . . . Indeed, such a breathtaking confrontation with a boundlessness in which we also experience an equally powerful totality is a motif that continually links the painters of the Romantic Sublime with a group of recent American painters who seek out what might be called the “Abstract Sublime.” In the context of two sea meditations by two great Romantic painters, Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea of about 1809 and Joseph Mallord William Turner’s Evening Star, Mark Rothko’s Light Earth over Blue of 1954 reveals affinities of vision and feeling. . . . Rothko, like Friedrich and Turner, places us on the threshold of those shapeless infinities discussed by the estheticians of the Sublime.[2]

Though the Enclave paintings of Hearns remain attached to the discourses surrounding the “Romantic sublime” and “abstract sublime,” their architectural titles expand the possibilities of interpretation. Camber, for instance, reveals a pulsating orchestration of patches of blues, greys and creams. The picture surface here is punctuated through the irregularity of the partially arched motif rendered in charcoal grey, bisecting the composition vertically, as if the distinctions between the voussoirs, extrados and impost of an architectural structure have been dissolved through the process of Surrealist automatism—expression that is spontaneous, unedited and aims toward the unconscious. Having thus attached the volatility of mark-making to the linguistic signifier “camber,” this painting of Hearns interrogates the problematic of visual representation.

Richard Hearns, Extrados, 2021. Oil on canvas, 178 by 132 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Cadogan Contemporary, London.

As the imagery of Enclave evokes translucence, haze, coats of fog, mist or steam, how are we to decode the architectural terms that Hearns has perplexingly assigned to the paintings? Along with the observer’s attempt in the detection of a given brushstroke as a signifier of a keystone or voussoir, or the reading of the set of gestural lines on the lower left corner of Keystone, for instance, as symbolic of transverse lines in perspectival representation of architectural planes, the paintings of Hearns activate a discourse between image and title, between gesture and speech. But internally as well, within the pictorial realm itself, there exists a dialectic between the purely painterly, formless gesture and the loosely geometricized phantom of the architectonic shape. In his expansive essay on perspectival representation, the following theoretical thoughts of Erwin Panofsky provide us with an insight on the recent painterly project of Hearns:

It is now finally clear that the perspectival view of space (and not merely perspectival construction) could also be contested from two quite different sides: Plato condemned it already in its modest beginnings because it distorted the “true proportions” of things, and replaced reality and the nomos (law) with subjective appearance and arbitrariness; whereas the most modern aesthetic thinking accuses it, on the contrary, of being the tool of a limited and limiting rationalism.[3]

Since a given work of the Enclave series consists of the dichotomy of the visual and verbal, it also brings to mind two of the momentous theoretical texts of Hubert Damisch: A Theory of /Cloud/ and The Origin of Perspective. While the former book of Damisch compellingly addresses visual representation through Renaissance and Baroque paintings based upon semiological analysis, the latter focuses upon the epistemological tenets of architectural representation of the Renaissance. With such architectural titles as Keystone, Camber, Mount, Corbel, Voussoir, Intrados and Extrados assigned to paintings that embody gestural abstraction, an attempt to interpret this corpus of Hearns through the methodology of semiotics seems to be particularly pertinent.

Richard Hearns, Intrados, 2020. Oil on canvas, 132 by 178 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Cadogan Contemporary, London.

As theorized by Ferdinand de Saussure at the outset of the twentieth century, the formation of meaning can be explained as relying upon a differential system, one that can further be extended to such signifiers as: architecture versus cloud, the measurable versus immeasurable, the definable versus undefinable, illusion versus abstraction. It is such a semiotic or structuralist set of concepts upon which Damisch bases his discourse in the afore-mentioned books, although phenomenological and philosophical thoughts throughout both texts of Damisch ultimately guide the reader toward a poststructuralist direction, whereby the interpretation of art incorporates the essence of formalism and broader epistemological inquiries. Damisch describes Brunelleschi’s first experiment on one-point perspective by writing,

On a small panel (tavoletta) about half a meter square, Brunelleschi had produced a painting in imitation (assimilitudine) of the baptistery of San Giovanni, in which he had depicted whatever his eye could seize upon from one particular vantage point . . . But Brunelleschi made no attempt to depict the sky; he merely showed it (dimostrare) . . . When the observer applied his eye to the back of the panel and, through the peephole made at the vanishing point of the composition, looked at the reflection of the painted image in a mirror placed at the appropriate distance, all that he in fact saw of the “sky” was the reflection of a reflection.[4]

Hence it is the shapelessness and temporally conditioned nature of the sky and cloud that suffices to signal at pictorial representation’s phenomenological paradox. Having assigned an architectural title to an otherwise primarily abstract expressionistic painting, Keystone generates interchanges among the reality of the exterior world, our visual perception of it, and the possibilities of pictorial representation. “Perspective only needs to ‘know’ things that it can reduce to its own order, things that occupy a place and the contour of which can be defined by lines. But the sky does not occupy a place, and cannot be measured; and as for clouds, nor can their outlines be fixed or their shapes analyzed in terms of surfaces,” writes Damisch. “A cloud belongs to the class of ‘bodies without surfaces,’ as Leonardo da Vinci was to put it, bodies that have no precise form or extremities and whose limits interpenetrate with those of other clouds.”[5]

Willem de Kooning, Montauk Highway, 1958. Oil and combined media on heavy paper mounted to canvas, 150 by 122 cm. Courtesy of Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California.

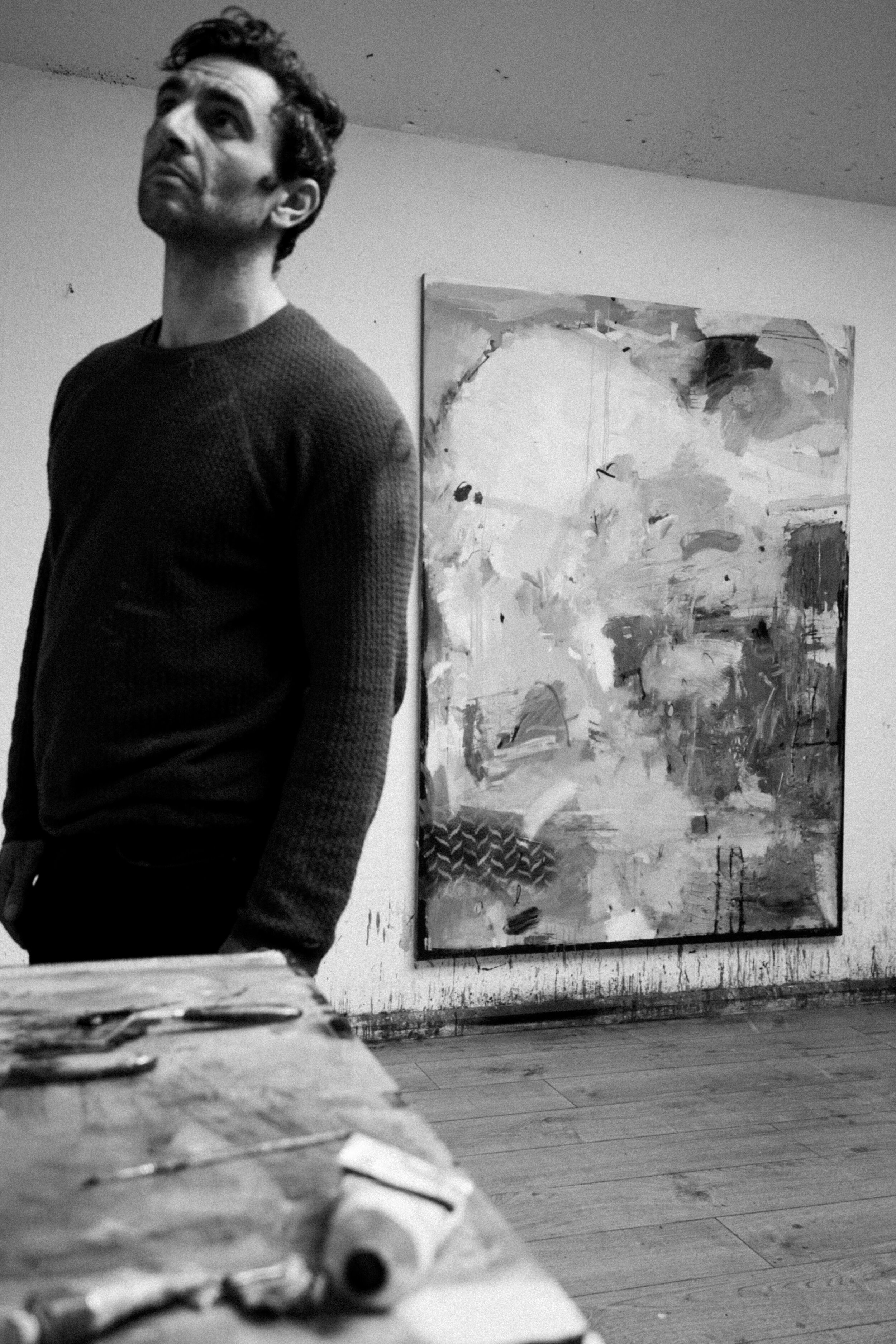

Richard Hearns carrying Intrados in the Burren National Park, County Clare, Ireland, 2021. Photograph by Eoin Collins. Courtesy of the artist and Cadogan Contemporary, London.

Through a series of arresting photographs, Eoin Collins has absorbingly captured the painted canvases of Hearns, exhibited outdoors, mounted upon the sedimentary rocks in the Burren National Park, located in northwestern County Clare in Ireland. Though the chromatically pulsating paintings of Hearns, with their rectangular formats, seem to resist to integrate visually with their primarily monochromatic backgrounds, a sense of amorphousness is conveyed through the paintings and their surrounding habitat. In other photographs by Collins, Hearns appears hauling a large canvas upon the hillside, where the sky asserts the illumination of tangible surfaces on the ground. “I make sense of paint. I journey with it. I live through the medium. For me there is sort of a salvation that exists in the act of painting,” Hearns has stated. We are here reminded of Rosenberg’s words: “The act-painting is of the same metaphysical substance as the artist’s existence. The new painting has broken down every distinction between art and life.”[6] And yet with architectural titles, the Enclave series of Hearns uncannily recalls the historical and theoretical tenets of Damisch. Within such color-drenched canvases as Intrados, Extrados, Voussoir, Corbel, Camber, Keystone and Mount, Hearns has incorporated gestural abstraction and architectonic forms, reframing our perception of pictorial representation. The Enclave paintings of Richard Hearns have rendered form and formlessness, architecture and cloud, history and observation, reference and autonomy decidedly discursive.

Corbel (2020) of Richard Hearns on display within the otherworldly geological region of the Burren National Park, County Clare, Ireland. Photograph by Eoin Collins. Courtesy of the artist and Cadogan Contemporary, London.

Notes

Harold Rosenberg, “The American Action Painters,” Art News 52 (December 1952), pp. 22-23 and 48-50.

Robert Rosenblum, “The Abstract Sublime,” Art News 59 (February 1961), pp. 38-41, 56 and 58.

Irwin Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form (1927), trans. Christopher S. Wood (New York: Zone Books, 1991), p. 71.

Hubert Damisch, A Theory of /Cloud/: Toward a History of Painting (1972), trans. Janet Lloyd (California: Stanford University Press: 2002), pp. 121-23.

Damisch, p. 124.

Rosenberg, p. 23.

Richard Hearns, Extrados (2021), photographed by Eoin Collins at the Burren National Park, County Clare, Ireland, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Cadogan Contemporary, London.